1.3 Odds and Ends

Notes on Art, Architecture, and the Pleasure of Work

Many of you know that we are renovating our home. About a year ago, Goodie and I began a project of reconfiguring the old floorplan of our farmhouse, which dates to 1917, and adding on another bedroom and bathroom. We’ve arrived at the beginning of November, and at last the end of the project appears in sight. After two weeks of painting (we have hired a crew that paints by hand. Most of our walls are still clad in the original tongue-and-groove beadboard, and it needs quite a bit more attention than I can give it), I’ll get back in and apply one more coat of polyurethane to the floors. Then, once we’re past tile work and appliance installation, we’ll plan our move in–hopefully sometime in late November, early December. Fingers crossed.

I won’t say this has been an easy project for us. In the beginning, we made the decision to hire a general contractor to handle the big ticket items: foundation, framing, kitchen design, etc. I couldn’t have done any of this without them, frankly. But I’ve still been left with a mountain of work to do: demolition, excavation (where do we put all that dirt?) flooring installation, exterior cladding and paint, floor finishing–sometimes the list feels like it will trail off into eternity. I’m somewhat comforted by the fact that one of the GC’s employees told me that I had done far more work than any of their previous clients. (What’s a human life, if it isn’t work?)

Our home, in process.

So: we’re pleased that things are moving along, despite limited resources, which include my own time and attention. All the same, it’s strange to walk around a modern home that’s half-finished. Floors are in; wall cladding is up; cabinets are hung; countertops are mostly done. As you peek around each room, you catch glimpses of what the interior will look like. This feels fun and exciting. But I have to say that there’s a part of me that misses being able to see what’s behind the walls: the old rough-cut wall studs, the door headers (or not); the countless illegible scribbles and pencil marks made by me or the workers we hired or the carpenters who built the house in 1917, or those who updated it in the 1960’s or again in the 1990’s. In the coming weeks, paints and varnishes will be on. I worry I’ll forget what the house looks like underneath. I want to remember this hidden labor, somehow, even if it isn’t my own, even if I will never see it again.

So much of modern construction is about hiding the work of construction: paint, caulk, drywall, wall cladding of any kind; the tedium of blending joints of siding (interior and exterior) so that you can’t see where one ends and another begins; sanding down the uneven edges of a floor; applying coats of polyurethane to protect but also hide imperfections in wood; finding the right trim to cover a seam in a wall, the floor, or ceiling. It’s not clear to me that the casualties of labor on the finished product—all the myriad dings, scrapes, and gouges that gather with greater frequency as you get closer to finishing your home—it’s not clear that the work of hiding them ever goes away. And yet the worst must be covered up or obscured before you move in. If you’ve built your house competently, all the plumbing, electrical and framing are hidden by the end of the project. You simple can’t live in a house these days–in most places, county and city authorities won’t let you, I mean–without any one of these things.

If I were to set out to classify just how many tasks and hours were spent hiding, erasing, or obscuring the actual work of building, I wouldn’t be surprised if they exceeded the tasks and hours involved in building the thing in the first place. And why shouldn’t it be this way? We all want our homes to be beautiful places we enjoy living in, and making things beautiful takes time and labor. Still, there’s something that troubles me about so much occlusion in my own home. It’s my hunch that for most of human history we haven’t built things this way.

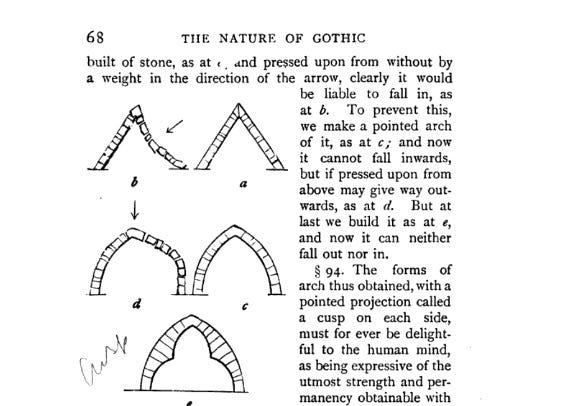

John Ruskin, the Victorian writer and art critic, was famous for lamenting the disaggregation of structural form and external design in industrial Britain. The middle and upper classes, he thought, spent far too much effort acquiring finely finished artifacts and decorations that were functionally useless; the ubiquitous glass baubles of the period were his example. By contrast, he praised medieval Gothic architecture for having perfected an integration of structure and design. The pointed arch is probably the most obvious instance. Pointed arches initially didn’t have any decoration. But by applying patterns of foliation to the design, medieval stonemasons ended up developing an architectural form that was far more structurally powerful than what had come before. Foliated arches are also quite striking and beautiful, and they became a standard feature of Gothic design and the “naturalism” that Ruskin described as integral to medieval aesthetics and architecture.

Ruskin’s arches. Foliated arch is at the bottom.

You don’t need to go back to Ruskin, the Arts and Crafts movement, or medieval stonemasons for examples of the integration of form and design, though. Just this past week I took my son, John, to a spoon carving class at the home of Elia Bizzari, a well known Windsor chairmaker in our region. There was so much to look at and to learn, but I couldn’t get over the elegance of one particular timber-framed joint that connected the post of a shed roof to the roof’s supporting member. (After searching around on Google, I still can’t find it. Maybe Elia just made it up?) I’d never seen a anything like it: it had two deep notches in the post that tapered down to two fine points. The support was whittled down to the same shape—two sloping claws—and Elia somehow got it fit inside the post perfectly. Now compare this to the cheap metal plates that are used to join the same members in modern construction. These are typically covered up with fascia, soffit, and other pieces of exterior trim. It’s obvious which one is more beautiful; which takes more time, skill, attention, and love; which one you’d rather display, proudly, on the entrance to your workshop, and which one you’d rather cover up with nails, boards, and paint.

Mark Turpin is a Bay Area carpenter and a poet who wrote in the 90’s and early 2000’s. I have no idea if he still writes, but he has a poem called “The Box” that speaks to the forms of occlusion and hiding that are an integral part of modern construction, and the ways that this occlusion can bleed into other forms of social and cultural erasure. It goes like this:

When I see driven nails I think of the hammer and the hand,

his mood, the weather, the time of year, what he packed

for lunch, how built up was the house,

the neighborhood, could he see another job from here?

And where was the lumber stacked, in what closet

stood the nail kegs, where did the boss unroll

the plans, which room was chosen for lunch? And where

did the sun strike first? Which wall cut the wind?

What was the picture in his mind as the hammer

hit the nail? A conversation? Another joke, a cigarette

or Friday, getting drunk, a woman, his wife, his youngest

kid or a side job he planned to make ends meet?

Maybe he pictured just the nail,

the slight swirl in the center of the head and raised

the hammer, and brought it down with fury and with skill

and sank it with a single blow.

Not a difficult trick for a journeyman, no harder

than figuring stairs or a hip-and-valley roof

or staking out a lot, but neither is a house,

a house is just a box fastened with thousands of nails.

The speaker of the poem, which I take to be Turpin, is on the jobsite somewhere, pausing perhaps to look at the old work of a previous carpenter. He can’t help but bring himself to consider the lives of the people, likely long dead, who built the home he is working on. Which room of the house did they eat lunch in, he asks, and the question may strike you as odd until you see framers doing this very thing in a house under construction. Of course, it’s not a room when they’re eating lunch in it; it’s probably just floor joists covered over with plywood subfloor. (“A house is just a box fastened with thousands of nails.”) Suffice it to say that it’s taboo for carpenters on the job to eat inside a finished home that isn’t theirs or someone’s that they know. Turpin’s question points to the jarring experience of stopping to think about what’s behind all the beautiful finishes and paint. It’s not pretty work, Turpin seems to say, and yet the work itself still carries with it dignity and skill. The problem is that the carpenter’s dignity and skill will lie hidden to virtually everyone who will live in the home. The only person to see it, to notice it, is the speaker, or perhaps the next carpenter who comes along to fix something that breaks down.

Countless acts of labor and attention lie hidden in a house. They remain, thank goodness, despite our attempts to hide them. But modern construction converts the skill of the framer or a carpenter into an assumption rather than an integral feature of a home’s aesthetic appeal or design. The homeowner can’t see how the home was made, but they can assume that it won’t break or fall down because they hired a credible company or an inspector before buying it. The assumption is underwritten by various forms of liability insurance purchased by the homeowner. The life of the carpenter, and the pleasure he or she may have taken in their work, have no other role to play.

The problem with this arrangement is that the forms of erasure that are involved in modern homebuilding can merge seamlessly with other forms of erasure (social, economic, racial) without our ever noticing. I take it that this is what Turpin’s poem, and many of his other poems, are about. It’s an issue that brings us back to Ruskin, who argued that the disaggregation of form and design was a sign that a system of “slavery” (he was thinking of the slavery of ancient Greece and industrial Britain) governed the conditions of labor that produced a given object or building. If workers have the freedom to make what they like, they will produce beautiful things that last as long as possible or is sensible. The integration of structure and design is human labor’s natural goal. And there will be endless variety. Take workers’ freedom away, make the labor compulsory, and embed the work in the factory floor, and the product will be perfectly uniform and boring. Ruskin takes Venetian glass to be a counterpoint. The skilled glassblower makes objects out of glass that is crude, wavy, and imperfect compared to the industrial glass of Britain (perfectly clear, uniform, refined). Yet visit the workshop of one of these artisans, Ruskin says, and you will see levels of intelligence and skill that have no equal in the factories of London. No two objects are alike: “[the Venetian artisan] cared not a whit whether his edges were sharp or not, but he invented a new design for every glass that he made, and never moulded a handle or a lip without a new fancy in it.” He goes on: “Choose whether you will pay for the lovely form or the perfect finish, and choose at the same moment whether you will make the worker a man or a grindstone” (The Nature of Gothic, 18).

Ruskin’s appeal to the moral sensibility of the well-heeled consumer makes it obvious whom he is writing for. Unlike Cobbett and the radicals of the previous two generation, Ruskin was unable to recognize the deep social and economic problems for what they were. Even still, there’s much more to say: about Ruskin’s ideas, about labor, industrialization, and aesthetics. I’d like to save these concerns for another time, though, and end with a quote from William Morris—one of my heroes, as it happens, a designer, writer, and a socialist whose printing press produced a beautiful edition of Ruskin’s “The Nature of Gothic” in 1892. Here is Morris, summing up Ruskin’s philosophy of art:

Art is the expression of man’s pleasure in labour. [...] It is possible for man to rejoice in his work, for, strange as it may seem to us to-day, there have been times when he did rejoice in it; and [...] unless man’s work once again becomes a pleasure to him, the token of which change will be that beauty is once again a natural and necessary accompaniment of productive labour, all but the worthless must toil in pain, and therefore live in pain. So that the result of the thousands of years of man’s effort on the earth must be general unhappiness and universal degradation–unhappiness and degradation, the conscious burden of which will grow in proportion to the growth of man’s intelligence, knowledge, and power over material nature,” Preface to The Nature of Gothic, viii.

That beauty be “a natural and necessary accompaniment” of our labor—may it be ever so for all of us.

J