2.2 Rivers of Oil

Fossil fuels, climate change, and the places we call home

Man’s power over Nature turns out to be a power exercised by some men over other men with Nature as its instrument. C.S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man

Three months ago, Dominion Energy proposed the construction of a 600-acre liquified natural gas (LNG) storage facility in southwestern Person County, a few miles from the Granville County border and about seven miles from our farm. The site would serve as a reservoir for energy production when demand spikes in the region. According to the company’s press release, the facility is designed to rapidly cool natural gas to negative 260 degrees Fahrenheit, a temperature at which the gas transforms into liquid. LNG takes up six hundred times less space than gas. Housing at least one twenty-five-million gallon tank (online, an “artistic rendering” shows a gigantic white cylinder towering hundreds of feet up into the air), the facility will receive gas from the Transco pipeline, which runs fracked gas across the eastern seaboard–all the way from Houston, Texas to New York City.

Many of the details of the project have been kept secret until very recently. I first started hearing rumors about the project from other farmers, who were noticing unusual activity on land adjacent to their own: rich-looking people in orange hats and vests, tromping around noisily in the woods. On December 5th, 2023, Person County commissioners rushed a public hearing and voted on Dominion’s proposal. According to NC Newsline, approximately three hundred and fifty people showed up in protest. Online, over a thousand people had signed a petition to stop the project. But when the proposal came to vote, commissioners agreed unanimously to allow Dominion’s project to go forward. Construction will begin soon.

The story of Dominion’s gas storage facility is a story that has played out in countless ways across the South: large, capital-intensive infrastructure deals being worked out by elites under cover of night, with no regard for the people who will have to live in close proximity to such projects. Still, there’s something almost quaint about Dominion’s desire for its project to stay hidden from public view. The last two years have been a boon to the natural gas industry in the United States. Currently, there are 173 LNG storage facilities scattered across the United States. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), global LNG storage capacity is set to increase by 25% across 2025 and 2026. At the helm of this expansion is the United States, who in a year or two will become the largest global exporter of LNG in the world. When Russia invaded Ukraine, the countries that make up the European Union swiftly became the largest customers for US LNG. Since then, the number of LNG storage and export terminals on the east coast has swollen to eight. Late in 2023, the Biden administration announced the approval of twenty new LNG storage and export facilities–nearly three times the number that currently exist.

LNG facilities, both for storage and export, are relatively new phenomena. Researchers are still coming to grips with their environmental impact. One peer-reviewed article suggests that anyone living within a two-kilometer zone of a storage and export facility is at high risk for cancer and respiratory disease. Again, Dominion’s facility would just be for storage, not export. As far as I am aware, no research has been done on those living close to facilities that just store the gas. Still, the company expects its facility to belch 65,000 tons of greenhouse gas each year–roughly the equivalent of 14,000 new combustion engines on the road. Nearly all of this greenhouse gas will be methane, which is eighty times more potent than CO2. It seems to me that Dominion’s figure does not include the other environmental costs of fracking, piping, and combusting, nor does it reckon with the high energy costs of supercooling the gas in the first place. And nowhere has Dominion acknowledged the risk its facility will pose to local watersheds. Bull City Public Investigators point out that the site in Person County is a “conglomeration” of six different parcels that lie at “the headwaters of a tributary of the Flat River.” The Flat River feeds Lake Michie. Lake Michie and the Little River Reservoir are the main sources of Durham’s drinking water. Dominion’s project will almost certainly ruin the pristine quality of the Flat River (again, via BCPI, the Flat has a 92 out of 100 rating for water quality. My readers of Durham and Cary: please read the BCPI report on PFAS and forever chemicals in your drinking water.)

In its press release, Dominion has claimed that the LNG storage project responds to a need it discerned within the sixteen-state region of its operation. This need is inherently domestic; none of the gas stored in the facility, it says, will be exported abroad. The gas that will be stored there will come from the fracked mountainsides of northern Appalachia. For whom exactly is this comforting news? Nevertheless, the disclosure raises the interesting question of how exactly the global fossil fuel industry relates to the places we call home. In considering Dominion’s storage facility and its proximity to our farm, it’s impossible not to feel the weight of global crises bearing down on this poor, rural corner of the Carolina Piedmont. But might it not be the case that they already depended on each other in ways that are typically hidden?

***

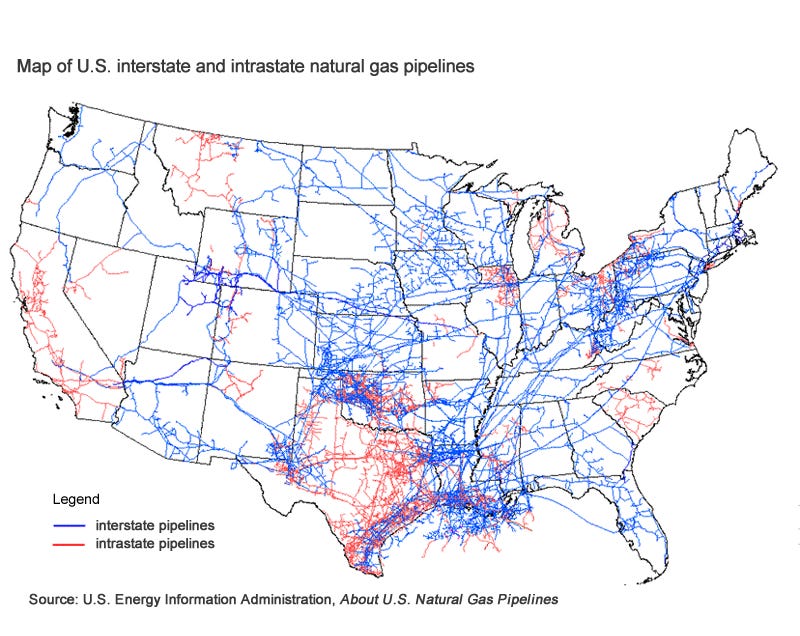

The oil and gas industry in the United States relies a network of pipelines that spread from the Gulf of Mexico to regions up and down the Atlantic coast. The IEA reports that this network is made up of three million miles of pipeline. The pipelines link sites of oil and gas extraction and production with hundreds of storage facilities and millions of individual consumers. A map of them resembles a map of a human being’s vascular system. If the continent were a living, breathing body, the Gulf of Mexico is where the heart should be. Red and blue lines of crude and gas fan out from the Gulf to the north, west, and east. North Carolina resembles a distant appendage: it’s receiving oil and gas, but they don’t travel anywhere else.

Estimates suggest that beneath the Gulf lie 3.44 billion barrels of oil and 5.7 trillion cubic feet of gas we’ve not yet tapped. The Gulf contains such huge reserves because, for millions of years, the Mississippi River system dumped minerals and organic matter into the alluvial plains of southern Louisiana and Mississippi. The trickling down of this effluvia fed immense colonies of plankton and algae. With decay, age, and pressure, the dead bodies of these organisms fossilized and were transformed into gas and oil.

What the rivers carried to the delta is mined, refined, and pumped away back north. The geographic patterns of fossil fuel extraction and distribution have reversed the ecological drift of millenia. But this is hardly a reversal; there’s no return of nutrients or energy. Those minerals and dead organisms, subjected to eons of pressure, are carried away and burned elsewhere. In a flash, the energy contained in them is gone, and their gaseous byproducts dissipate into the atmosphere. What took the continent millenia to produce beneath the sea has taken human beings just a few decades to unmake. (“Counting from 1751 to 2010, half of all CO2 emissions from the combustion of fossil fuels occurred after 1986, in just twenty-five years, when one of the greatest research efforts in history produced the science of climate change,” Andreas Malm, Fossil Capital, 238.)

The map of pipeline infrastructure reads to me like a supra-ecological parody. Imagine for a moment that the drawing of interstate and coastal boundaries are gone; all that remains is the pipeline network. Where are the rivers, the mountains, and the plains? We know that these fuels emanate from the Gulf. But topography, geology, hydrology make little difference to the supply and demand of fossil fuels. The pipelines make their own spatial logic; energy demand dictates where and how and when the fuels will travel. Looking at the map, we can guess where the Rocky Mountains or New York City or Chicago or DC might be because we know that this is supposed to be a map of the United States. But otherwise the map is shockingly placeless.

The French sociologist, Henri Lefebvre, argued that capitalist economies destroyed the naturalness of human spaces. Not that long ago, we chose to construct buildings and towns and monuments in relation to natural features that we deemed meaningful for spiritual or agricultural reasons. Think of the monastery on top of a cliff; the cathedral at the center of a town; the town in a bend in a river. The primitive accumulation of capital–expulsion of peasants, expropriation of commons, the generation of a landless workforce–transforms the way we plan and build the world around us. Spaces are organized now on the maximization of exchange value: how might a given location maximize profits for a given industry? Lefebvre calls the type of space capitalist societies produce abstract space.

Like oil and gas pipelines, abstract space imposes its own logic on the landscape. Durham, North Carolina is a classic example of a city dominated by abstract space. Durham grew up because it was a crossroads in the developing tobacco economy. Perhaps its only significance was that there were already railroads here (railroads being a kind of proto-pipeline for the distribution of capital and labor). Certainly, Durham did not become a city because of any natural feature like a mountain, a valley, or fertile soil. Having grown up by a river, I am sometimes bothered by the fact that when I drive around Durham I can’t place myself in relation to a natural landmark.

A map of the Transco pipeline.

At the same time, though, when I look back at the map, I can’t help feeling like I know the route of a couple of these pipelines intimately–or perhaps that they know something about me, or that they anticipate some aspect of my life. Earlier I mentioned the Transco pipeline, which runs from Houston to New York. It passes a few miles from our farm. The arc it traces across the Southeast mimics the interstate arc of I-85 to I-20, a route I have taken dozens of times with my car when I travel home to Mississippi from Virginia or, more currently, North Carolina. Now, with the storage facility placed distinctly in the pipeline’s path, my own place, the region where I farm, is marked as a node on the arterial pathways of energy infrastructure. So it seems that the geographic contours of my own life–its pathways in the South–have an uncanny alter-image beneath the surface of the earth.

To what extent should this image be part of my own sense of who I am? Fossil fuels and their infrastructure have enabled my life and the lives of my family; the pipeline runs along the pathways I have chosen to take thus far in my life. Has it ever not been so for the last hundred years? Do these pathways not also trace a kind of shadow life of individuals, of a society, of a civilization? It’s a life measured not by miles but by cumulative environmental force. Might that shadow life be, from a certain perspective, the permanent, the more lasting account?

Energy from fossil fuels courses above our heads and under our roads, our driveways, and our homes. It pulses in the wires behind walls, inside appliances, and in our cars. Its byproducts are in our air, our soils, our water, and our lungs. Oil and its afterlives are unheimlich, not-homely, uncanny. The novelist, Amitav Ghosh, has spoken of climate change as the “environmental uncanny”: the mysterious work of our own hands that returns to haunt us in ecological and climatological forms. Tracing the patterns of the environmental uncanny means picturing a parodic inversion of ecological history.

A chief characteristic of oil is its lubricity. We subject it to intense hydraulic flows that spread the substance across our continent. This is a background condition of modern life. Is it merely a coincidence that so many of our lives feel subject to the same frictionless, pressurized force?

Thank you for getting me up to speed on this topic. It gets real and personal when it impacts the safety of our food supply, and the land that I know we want to have set aside for regenerative farming practices.