2.3 John Clare's Animal Poems: Part 1

To the Snipe

“Birds bees trees flowers all talked to me incessantly louder than the busy hum of men and who so wise as nature out of doors on the green grass by woods and streams under the beautiful sunny sky–daily communings with God and not a word spoken.” John Clare, letter dated to 1848 or 1849, Northampton General Lunatic Asylum

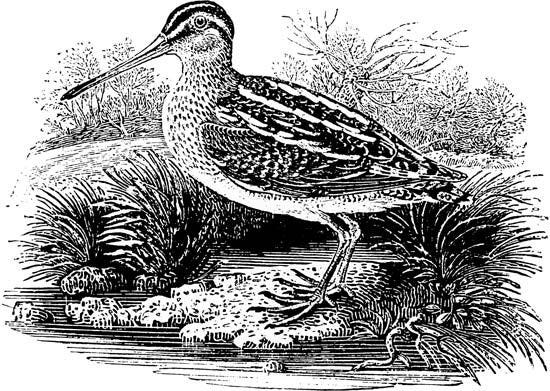

The only way I know how to begin talking about my love of the poet, John Clare [1793-1864], is by taking you directly to one of his poems. In the first part of this essay, I’ll be discussing a poem he wrote about the snipe, a water loving bird that prefers to make its home in marshy regions far from human settlement. So that you can better imagine the bird Clare writes about, I’ve included a woodcut of a snipe by Thomas Bewick [1753-1828], an English artist and an engraver whose life overlapped for the first thirty years of Clare’s own. The woodcut was produced in 1797. In case you’d like to read the poem before I begin talking about it, here is a link to it.

The Common Snipe, by Thomas Bewick. Wood engraving. 1797.

Clare’s poem begins by addressing the bird in a four-line sentence fragment that, like most of his poetry, contains no punctuation except the dash:

Lover of swamps

The quagmire overgrown

With hassock tufts of sedge–where fear encamps

Around thy home alone

Snipes love overgrown swamps; no main verb or predicate in the first two lines, but Clare’s meaning seems simple enough. The specific “quagmire” Clare has in mind is a place called Whittlesey Mere, a vast, two-thousand acre wilderness (a “mere” is a lake) whose western border lay ten miles from the village where Clare lived. The mere was one of the largest inland lakes in England, and it was home to countless species of fish, waterfowl, and marshy vegetation. Clare would spend the day walking from his village to the mere, where he roamed and took notes on loose scraps of paper about the different ferns, mosses, and waterfowl he saw. Later, in 1853, Whittlesey was drained and turned into cropland by the son of one of Clare’s patrons.

But first: back to the poem. Looking beyond those first two lines, questions start to emerge. What does this lover of swamps and quagmires have to do with a “fear” that camps around its home–around “thy” home alone, Clare says? How do love, home, and fear go together so closely for this particular species of bird? If it is fearful of anything, it must be the speaker, the speaker’s kind, or perhaps the name humans have given it. (The bird’s identity is given exactly once: outside of the poem, in its title.) If we’re being honest readers, at this point in the poem, all we know is that this bird is a “lover” of a particular kind of marshy place—as far away from human habitation as possible. And so it seems that the poem’s apostrophe, the direct address to the snipe (“thee,” “thy,” etc.), wobbles in its gesture of intimacy. The poet speaks to the snipe; the snipe goes silent.

In stanza two, it turns out that snipe territory isn’t meant to receive the plodding gait of men. Where the snipe lives happily, the marsh grass quakes–trembles–under “human foot”:

The trembling grass

Quakes from the human foot

Nor bears the weight of man to let him pass

Where he alone and mute

Sitteth at rest

In safety neath the clump

Of hugh flag-forrest that thy haunts invest

Or some old sallow stump

The human speaker passes by, barely able to find footing, while the snipe “sitteth at rest/In safety” among the “hugh” (Clare’s dialectical spelling of “huge”) forest of “flag,” or sedge grass. When the poet speaks, the snipe is withdrawn, “alone and mute,” an animal very different from the trilling nightingale. The watery wilderness of snipe country is a scene of domestic intimacy and bliss to one species of bird; that intimacy is disturbed by the tread of humans. To the human passerby, the marsh is an alien world, a place merely to pass through, where human passing (trespassing on waste land? Or is it poetry?) is dogged by uncertainty and imprecision. Holding together those two forms of the same world, the same marsh or mere, seems to threaten the bird’s life and to disintegrate the speaker’s ambition. It is in the turgid waters of the marsh, after all, that we find the snipe–not the poem’s speaker–

Thriving on seams

That tiney islands swell

Just hilling from the mud and rancid streams

Suiting thy nature well

For here thy bill

Suited by wisdom good

Of rude unseemly length doth delve and drill

The gelid mass for food

Where humans can’t make a way, the snipe thrives. In the mere, the snipe does what God (“suited by wisdom good”) designed it to do: to “delve” and “drill” the “gelid” [icy] muck for food. Here, surrounded by tufts of grass, at home in the wet, cold wilderness, its “unseemly” bill pokes and sifts through the refuse and decay of organic matter, searching for little bits to eat. For Clare, this makes the success of the snipe’s domesticity all the more “mystic” and strange: the little “isles” of marsh grass, beaten and shaken by sudden and unpredictable squalls (“tempests howl/ around each flaggy plot”), are hardly different than “isles that ocean make.” Yet somehow in the “flag-hidden lake,” far from “man,” “boy,” and “[live]stock,” the snipe finds a place “in the moors rude desolate and spungy lap” to hide, make a nest, and feed its young. “Tis power divine,” Clare muses, which makes them brave enough to endure “the roughest tempest and at ease recline/On marshes or the wave” and rear their babies.

But what about the snipe’s fear? If it’s a “power divine” that makes the snipe able to endure the marsh’s unforgiving weather with “peace” and “calm,” what are we to make about the bird’s shyness towards humans? In the very next stanza, Clare avers that “instinct knows/Not safetys bounds to shun/The firmer ground where skulking fowler goes/With searching dogs and gun.” The same “power” or “instinct” that makes a snipe well adapted to life on the marsh makes it vulnerable to predation, human or otherwise.

Clare is hardly a “skulking fowler” on the mere, but something about his trespassing on the snipe’s territory raises the issue of how it could make sense to speak of the snipe’s world and the human world together–and the possibility of the sort of poem Clare is trying to write. Despite the mere’s austere beauty, the world of the mere isn’t Clare’s, and it’s a mistake (a dangerous one, to him and to the marsh’s inhabitants) to suppose that it could ever belong to humans. The snipe is like a flower that withers at the slightest touch. When the poet reaches out in love and attention, the bird retreats into the safety of silence and stillness. The mere, a broad and watery expanse, discloses itself in fragments. It sinks under the poet’s plodding foot. To talk of humans sharing a world with a wilderness like this is to speak of some other world that Clare doesn’t belong to. When Clare admonish the snipe for venturing too close to “tepid springs/Scarcely one stride across,” he seems to admit as much:

And never chuse

The little sinky foss

Streaking the moores whence spa-red water spews

From puddles fringed with moss

Free booters there

Intent to kill and slay

Startle with cracking guns the trepid air

And dogs thy haunts betray

Never choose, Clare says, that little ditch men dug to channel water out of the mere. The water that “spews” from its puddles has turned an uncanny “spa-red.” Is the ditch polluted? If there is pollution, it’s not from any factory. Maybe it is blood, not so much from slain waterfowl (Clare mentions “widgeon and teal/ and wild duck”) but from the digging and delving of the land by the same agricultural “improvers” who “startle with cracking guns.” There is perhaps a blurring of identity between the improvers and the hunters: both are members of the same economic class. From the perspective of the snipe and the mere, hunting and habitat loss belong to the same, violent, terraforming strategy of enclosure and “improvement.”

Where is the verse-making interloper in all of this? After appealing to the snipe to stay away from humankind, the speaker takes his leave of the bird’s company (if we can call it company) and offers up the following reflection:

In these thy haunts

Ive gleaned habitual love

From the vague world where pride and folly taunts

I muse and look above

Thy solitudes

The unbounded heaven esteems

And here my heart warms into higher moods

And dignifying dreams

I see the sky

Smile on the meanest spot

Giving to all that creep or walk or flye

A calm and cordial lot

Thine teaches me

Right feelings to employ

That in the dreariest places peace will be

A dweller and a joy

***

John Clare was born in the village of Helpstone in Northamptonshire, England, in July of 1793. His father, Parker Clare, was the illegitimate son of John Parker, a local schoolteacher, and Alice Clare, the daughter of a local parish clerk. John was born in the same row of tenements that he would raise his own family in. The Clare home had no running water and one outdoor bathroom that the family shared with neighbors.

For as long as anyone in his family could remember, the Clare clan were farm laborers. A laborer was distinct from a cottager, a farmer, tenant, or landowner; these maintained some control over land through rent, ownership, or ancestral claim. The name Clare comes from the word clayer, which refers to the act of improving soil by adding marl, or clay, to it. John attended the local parish school until age eleven or twelve. From then on his life was dominated by the seasonal rhythms of agricultural work. As a boy, he worked as a thresher, a bird-scarer, a ploughboy, “and a pot-scourer in a pub.” When he was older and more physically able, Clare worked in the fields with enclosure gangs, maintained a garden for a rich neighbor, and would eventually turn to burning lime to make money for his growing family.

At the age of thirteen, Clare began writing poetry. In an autobiographical sketch, Clare recalls a weaver friend from his village showing him a fragment of a poem by James Thomson called The Seasons (1720s). From then on, his life changed. He began writing poems about rural life and the natural scenery around his village and the open field, scribbling down rhyming couplets about places, objects, walks he had taken, and jobs he had done. In 1818, he was “discovered” by a local publisher, and in 1820 his first book of verse–Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery–was published by Taylor and Hessey, the same duo who published John Keats’s Poems in 1817.

In advertising Clare’s work, Taylor and Hessey billed Clare as “the Northamptonshire peasant poet.” This was a sobriquet Clare found hard to shake. For much of his life, he didn’t fight it, but the term disguised Clare’s own very complicated education and abilities. He was very well read, an excellent fiddler and collector of folk tunes, and in the early years of his literary career wined and dined with the literary and intellectual elites of London. He was also an accomplished if amateur naturalist. Clare planned and began work on, but never completed, a natural history of the Northamptonshire region. He became an expert in local flora and fauna, collected fossils, and he described many species of fern, flower, and moss that no one else knew about. He confessed to loathing the “dark system” of Carl Linnaeus [1707-1778]: the encyclopedic, classificatory system of binomial nomenclature popularized in the Enlightenment. As Clare’s biographer, Jonathan Bate, puts the matter, “the universalizing ambition of the system, with its complex Latin names and ‘systematic symbols,’ did not answer to his perception of the wild flowers peculiar to his own neighborhood. He saw flowers in their local, living environment” (103). What mattered to Clare was the ecological context and the medicinal use of plants.

John Clare, by Edward Scriven, after William Hilton. Stipple engraving, published 1821. (Source: National Portrait Gallery)

Despite these avocations, Clare was, for most of his life, crushingly poor. His first book was the only book of his that sold well, but he never made much money on it. He tended to write his poetry on whatever scraps of paper he could afford or find, like the backs of letters or envelopes. When he couldn’t afford paper, he developed a method for making his own out of birch bark. He also made his own ink out of “bruised nut galls, green copper, and stone blue soaked in a pint and a half of rain-water” (284). In some manuscripts, Clare’s homemade ink has eaten through the paper.

Bate says that Clare’s editor, John Taylor, frequently tried to expunge depictions of labor in Clare’s verse. But Clare thought it was central to the world he occupied and to the poetic tradition he claimed for himself (in letters he frequently references other laboring poets, like James Hogg and Robert Bloomfield). Even so, Clare had a hard time finding regular employment for himself, and he deeply resented some of the work he was forced to perform. Here’s an example: Clare’s work as a lime burner was in service to forces of economic and ecological transformation that he despised and attacked in his poetry. The agricultural lime he helped produce was used to sweeten soils on common or waste land that had recently been enclosed and turned into cropland. At times, though, his labor was even more directly linked to the enclosure and improvement that he despised. For several years, he worked on enclosure gangs that tore down hedges and demolished the open field system of traditional agriculture around his home in Helpstone. Some of his best and most important work is in the genre of “ecological protest,” to borrow EP Thompson’s term, against the transformation of the countryside around Helpstone. Helpstone was fully enclosed in 1820, the publication year of Clare’s first book. In the community’s final enclosure award, landowners “enumerated the ownership of every acre, rood, and perch, the position of every road, footway, and public drain” (48). In a poem called “The Mores,” Clare decries this system of financial tabulation that turned the natural world in a list of commodities to be traded in the marketplace:

Each little tyrant with his little sign

Shows where man claims earth glows no more divine

On paths to freedom and to childhood dear

A board sticks up to notice ‘no road here’

And on the tree with ivy overhung

The hated sign by vulgar taste is hung

As tho the very birds should learn to know

When they go there they must no further go

As I’ve said ad nauseam on this Substack, historians still debate the precise economic consequences of enclosure in this time period. As Clare’s lines suggests, though, enclosure of common and wasteland had profound social, political, and symbolic consequences. “Lawless laws” followed the “dreams of plunder” of the already rich. Property claims destroy the mysterious, divine “glow” of the earth. On a personal level, the loss of freedom also meant a loss of childhood: a convergence of endings (personal, ecological, social) which suggested that, for Clare, there was no going back.

By the mid 1830’s, Clare’s mental health had seriously deteriorated. After some possibly violent outbursts at home, Clare was brought to a private asylum in York, and later, after Clare escaped in 1841, to the public asylum at Northampton, where he would remain until his death in 1864. By 1837, Clare was occasionally gripped by the fantasy that he was Lord Byron, the most famous Romantic poet of the era; sometimes he claimed to be a prizefighting boxer. In letters written from the asylums, Clare wrote that he thought he was serving a sentence for bigamy. On the intake form at Northampton, Clare’s doctor wrote that Clare’s madness had come from “years [of being] addicted to poetical prosing.” At York, Clare’s doctor, Matthew Allen, offered a more humane assessment: the poet’s mental suffering was brought on by “his extreme poverty and over-exertion of body and mind.”

I don’t really have a desire to say more about the end of Clare’s life. It’s very sad. If you’re interested in learning more, I suggest that you take up Bate’s deeply humane treatment of it in his biography.

In the essays that will follow this one, I will be taking a look at some of the poems Clare wrote in the 1830’s. They are mostly about animals like the snipe. There’s something extraordinary about the later work. That’s not to say that his poetry from the 1810’s and ‘20’s isn’t lovely and essential. They display a remarkable facility with different genres, styles, and literary modes. By comparison, the late poetry is spare, simple, and austere. It is constantly striving for a perspective on the natural world from the bottom up. It offers up a perspective on human affairs that’s located somewhere outside the human, or what we might typically assume to be the human. And it’s in search of a language that might, in finding kinship with the nonhuman world, conjure up a restoration, if only imagined, between human beings and creation.