Ave atque Vale

In honor of a late bull

About a week before Christmas, I noticed that Breck, our bull, wasn’t feeling well. In the wintertime, after the cows finish grazing the grass I stockpile in the summer, I’ll cordon off an area of my farm that could use a little more trampling and disturbance. It’s usually on a part of the farm that is former pine plantation and now, four years after the timber was taken out, recovering pasture land. As the cows eat hay in this places, they usually have more space to roam than they do in the spring, summer, and fall, when rotations through the farm are tight and fast. In the spring, it’s not unusual for me to move them two or three times a day. In the winter, after the grass is gone, I’ll keep them locked in on spot for weeks, sometimes months.

Breck had separated himself from the herd and found a quiet corner down by the pond. He wasn’t down on the ground, at least not for abnormally long stretches of time, but he was standing with his legs kicked back in a stilted, “come-at-me” pose. It wasn’t until I got much closer that I saw the problem. If you look at a cow from behind it, the profile should be roughly the same shape as an egg would be if you stood it upright with the tip facing up. If the profile of your cow looks like an apple, then you have a problem. Breck’s entire left side, from the ribcage down, was horribly distended. It looked like he’d swallowed a barrel that got stuck 2/3 of the way down his digestive tract.

A sick cow is not to be trifled with, especially if the illness is bloat. One minute they seem like they might pull through. The next, they’re dead in the field. Cows are fine until they aren’t. I’ve learned the hard way that you have to be extremely aggressive at diagnosing symptoms and acting quickly.

After getting on the phone with a couple of vets and veteran farmers, I decided to give him a round of shots to boost his metabolism. I also gave him a bloat drench, orally, in the field, without a restraining device like a head gate. Maybe it wasn’t the wisest decision, but it was Breck, our beloved bull, probably the most docile animal we’ve ever had on the farm. Also, we don’t have a head gate or a chute to speak of. A good head gate is expensive. A solid head gate with a squeeze chute costs costs at least five or six thousand of dollars, so I have always found ways of making do without them.

This time, though, Breck resisted for a bit, pulling away and drifting from me until, after four or five tries, he walked over to a corner of the field and put his nose right up against the corner post so I couldn’t get around to his mouth. Eventually, I got him to take it by mixing it in a bucket with water and emptying his water trough.

Breck, at three years old, in 2021.

At first, everything worked. Ten hours later, the bloat had subsided and he was eating and drinking again. From behind, he looked like an egg again, not an apple. A day later, he had wandered back to the rest of the herd and was eating and drinking contentedly, behaving as he always does. But then something strange happened. The day after that, the bloat was back, and Breck was basically immobile on the ground. I tried to get him up and on the trailer to take him to the large animal veterinary hospital, but he wouldn’t budge. At this point, after a night on the ground, saddled with bloat, he was too weak to get up. He was down, as they say, and there was nothing I could to about it. The local vet was off for the week, and with the first round of bloat, the state vet wouldn’t come because I didn’t have a safe way to physically restrain him even though we pleaded with them. Though he is as meek as cows come, they wouldn’t risk it. I can’t blame them. By the time he got sick the second time, they had agreed to come out in four days after the Christmas holiday. I knew there was no way he’d last that long. I tried my best to keep him alive, but he didn’t make it. Breck died on December 30th, two days before the New Year. He was one of the greatest animals we’ve ever had on the farm. I will miss him so much.

It’s difficult to explain the loss of an animal like this. For years he was the cornerstone of our farm’s breeding program, our pride and joy, a very-old-line Black Angus Scottish bull that descended from the Wye Plantation at the University of Maryland, which has kept a closed herd of Black Angus cattle that came straight from Scotland back in the 50’s. He was small, stocky, the ideal type of animal for a grass-based cattle farm; none of the large-framed nonsense that has dominated the cattle market for the last fifty years.

There is the financial loss, then, and the loss of future genetics to the farm. But Breck was also a friend. I bought him through sheer dumb luck from a farmer friend who knows a lot more about cattle than I do. He’d had enough of the business and was selling out. I had the good sense to buy the bull he wanted to sell me. From day one, Breck was my lead animal. Anytime I needed to work the cattle or move them to a difficult place, he’d come running for a treat, and the rest would follow. Now that he’s gone, my relationship to the animals around me suddenly feels tenuous.

Normally, when a cow is resting on the ground, it will cock its head up and to the side so that the neck curls away from the ground. Its head is lifted up into the air above the body. When it sleeps, it will often wrap its head around rest it on its flank. Sometimes it will lay its head on the ground, but it will always do it with its neck curled. It does this to cut off the rumen. If a cow’s neck were laid out straight like you do when we sleep, the rumen would overwhelm the esophagus with hot liquid ferment. If a cow stays like this for too long, it won’t get up again. You’ve probably seen cows in the normal pose before without knowing what you were looking at. All cows do it, every single one, when they lay down to take a rest.

A strange thing happens when a cow is dying. It relaxes its neck, lies on one side, and lays its head flat on the ground. The body lies in profile with the earth, as if longing to be absorbed by it. A female cow will sometimes do this when giving birth. It’s a terrible thing to witness. If you live around cows and you see one do it, you know instantly that it is in pain. If it happens and you’re not they’re to catch it, the cow will almost certainly die. But then, if they are doing it, then they are pretty far gone to begin with. I’m told that they can lay like this for days, unwilling or at last unable to get up or lift their heads, until they finally die from drowning or dehydration.

There is nothing quite so devastating as walking out into the field and finding a cow prone like this. In my experience, when you get to this point, there’s not much to be done. Mercifully, it is not a frequent occurrence; twice it has happened to us over the last five years. But whenever it happens, it’s enough to make you want to hang it all and quit. When it’s an animal that I love, some small part of me is sundered and drifts off.

Is it possible to regrow parts of ourselves, like some creatures do? Or does a new chunk break off every time something or someone we love dies? Sometimes I worry that if I wait long enough, there won’t be anything left of my love for this place and the creatures who call it home.

There is an older farmer a few roads down from us that I have gotten to know well. He has helped us a lot over the years. I have tried to help him as best I can, though he doesn’t really need my help. Once, when a beloved calf of ours went lame and couldn’t stand up after days of helping her, he came over and shot it because I couldn’t bring myself to do it. I have seen him weep over the deaths of his own animals, large and small: horses, dogs, cats. When I hear his sobs through the telephone, I sometimes can’t believe that, after a lifetime of being surrounded by farm death, he still mourns.

I woke up early and knocked out the chores in the dark. Now, it’s cold and raining. The kids are at school. A car passes down the road with a sibilant whine, and I hear a whomp in front of the house. I dart out in the pricking rain, socks on my feet, no time for boots. Was it a dog, or a cat? Neither: just a squirrel, its body now a small, crumpled heap of fur and broken bone.

In the days leading up to Breck’s death, I slept terribly. Around 2:30 or 3am, I would wake up with an image of Breck’s body transfigured by pain, and I run to help pick his head up, but I couldn’t do anything. I’d sit on the ground and grimace and stare, then I’d wake up feeling like my heart had been torn out. Two nights ago I dreamt I had to shoot him. His body quivered and strained when I did it, each limb stretching, then slowly relaxed as blood and then shit welled around his backside. Earlier that day I had been out to see him and he had been nearly motionless this time--a little labored breathing, a quiver of foreleg. His mouth frothed slightly. I knew he would die soon. In another dream, I am walking back to the house and I pass through the gate to get home, and I realize I am surrounded by the corpses of my cattle herd.

After the day he died, I slept better than I had for weeks. Eleven uninterrupted hours. Does grief always work like this? A welling of pain that grows tumescent, then a long, slow release.

My son John this morning, before he left for school, gazed over at the old garden and said he saw a hawk “swimming” in the wind. He is nine now, and he is constantly searching for the edges of words, trying to figure out how they fit together. I came over and the two of us watched the hawk level over a wave of wind. We see an army of dead leaves come tumbling head over heels, as if in pursuit of us, and the same gust bursts across our faces. The leaves pass all around us and rush beyond, then settle back to the ground again.

We named Breck after Alan Stewart Breck, the hero of Kidnapped, the 1886 novel by Robert Louis Stevenson. It’s not my kids’ favorite Stephenson book, but Breck is our favorite Stephenson character, who is followed closely by Ol’ Barbecue himself, Long John Silver, of Treasure Island. Kidnapped, which is set in Scotland during the Highland Clearances, tells the story of a foundling boy named David Balfour, who after seeking refuge from a rich, crusty uncle is betrayed and sold into indentured servitude. David is bound and shuffled aboard a boat bound for “old Caroliny,” but before the ship manage to pull away from the Isles it strikes a small vessel in the fog, killing all but one of the people on board. It turns out that the man that didn’t die is a political fugitive: Alan Breck, a Jacobite assassin and sworn enemy of the British crown. Alan and David form a team; in no time, they overtake the boat through Breck’s swashbuckling prowess. Soon they are being pursued throughout Scottish Highlands, evading redcoats and assassinating officials of the Empire along the way.

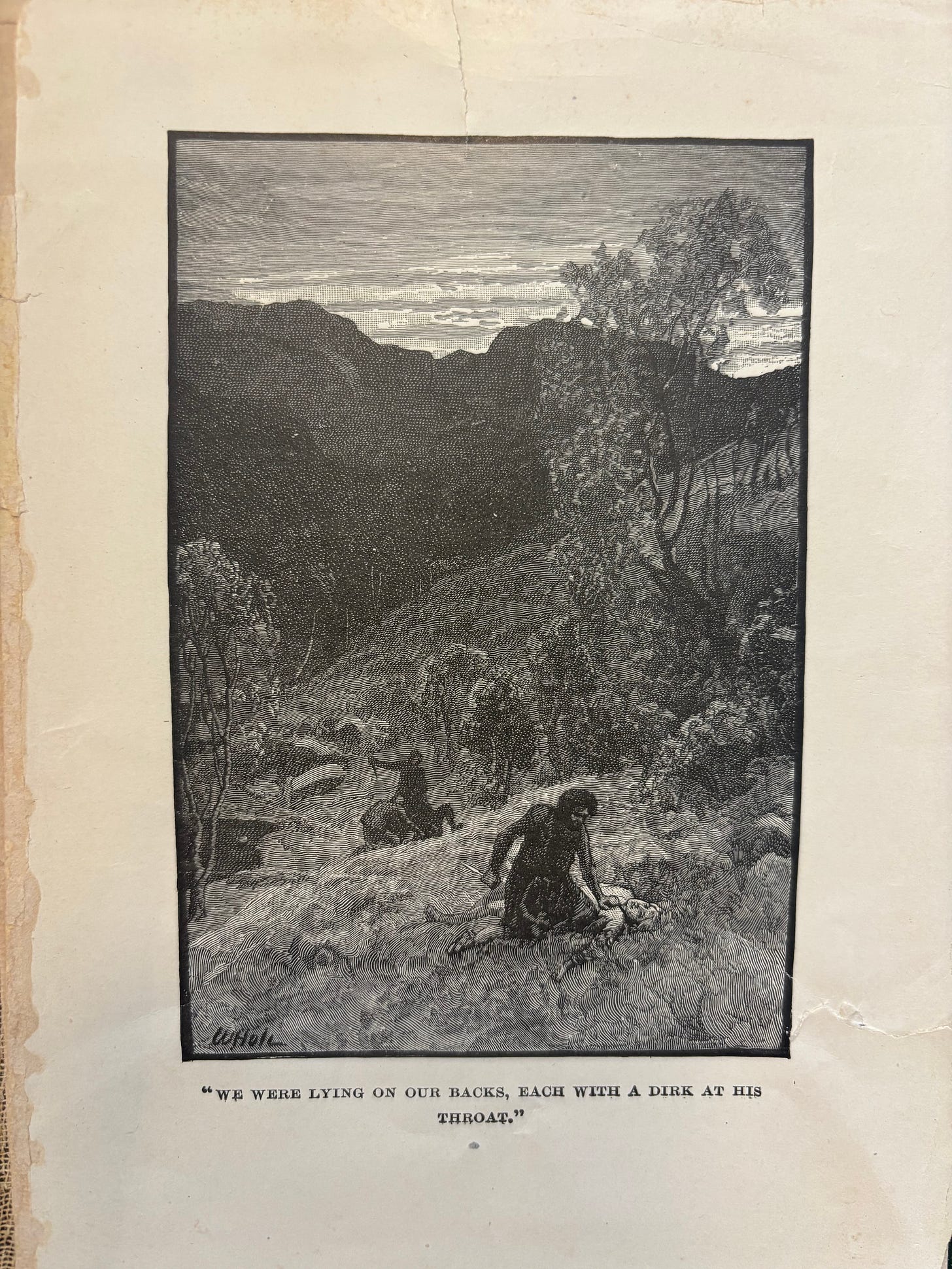

An illustration from the 1906 edition of Kidnapped, which our family uses.

The book ends with David recovering his stolen fortune from his uncle in Edinburgh, and Alan, through the solicitation of a spy, hears that he may find refuge in France. I’ll end this post by quoting the end of Kidnapped, when the two unlikely friends say goodbye to each other, followed by the “editor’s” (that is, Stevenson’s) postscript.

In the meanwhile Alan and I went slowly forward upon our way, having little heart either to walk or speak. The same thought was uppermost in both, that we were near the time of our parting; and rememberance of all the bygone days sat upon us sorely. We talked indeed of what should be done; and it was resolved that Alan should keep to the county, biding now here, now there, but coming once in a day to a particular place where I might be able to communicate with him, either in my own person or by messenger. In the meanwhile, I was to seek out a lawyer, who was an Appin Stewart, and a man therefore wholly to be trusted; and it should be his part to find a ship and arrange for Alan’s safe embarcation. No sooner was this business done, than the words seemed to leave us [...] We came the by-way over the hill of Corstorphine; and when we got near to the place called Rest-and-beThankful, and looked down on Corstorphine bogs and over to the city and the castle on the hill, we both stopped, for we both knew, without a word said, that we had come to where our ways parted. Here he repeated to me again what had been agreed upon between us: the address of the lawyer, the daily hour at which Alan might be found, and the signals that were to be made by any that came seeking him. Then I gave what money I had [...], so that he should not starve in the meanwhile; and then we stood a space, and looked over at Edinburgh in silence.

“Well, good-bye,” said Alan, and held out his left hand.

“Good-bye,” said I, and gave the hand a little grasp, and went off down hill.

Neither one of us looked the other in the face, nor so long as he was in my view did I take one back glance at the friend I was leaving. But as I went on my way to the city, I felt so lost and lonesome, that I could have found it in my heart to sit down by the dyke, and cry and weep like a baby.

It was coming near noon, when I passed in by the West Kirk and the Grassmarket into the streets of the capital. The huge height of the buildings, running up to ten and fifteen storeys, the narrow arched entries that continually vomited passengers, the wares of the merchants in their windows, the hubbub and endless stir, the foul smells and the fine clothes, and a hundred other particulars too small to mention, struck me into a kind of stupor of surprise, so that I let the crowd carry me to and fro; and yet all the time what I was thinking of was Alan at Rest-and-be-Thankful; and all the time (although you would think I would not choose but be delighted with these braws and novelties) there was a cold gnawing in my inside like a remorse for something wrong.

The hand of Providence brought me in my drifting to the very doors of the British Linen Company’s bank.

[Just there, with his hand upon his fortune, the present editor inclines for the time to say farewell to David. How Alan escaped, and what was done about the murder, with a variety of other delectable particulars, may be some day set forth. That is a thing, however, that hinges on the public fancy. The editor has a great kindness for both Alan and David, and would gladly spend much of his life in their society; but in this he may find himself to stand alone. In the fear of which, and lest any one should complain of scurvy usage, he hastens to protest that all went well with both, in the limited and human sense of the word “well;” that whatever befell them, it was not dishonour, and whatever failed them, they were not found wanting to themselves.]

Alan Breck, waiting for David Balfour to leap.

Hey Jack - Your Breck ....

Each love we hold includes

Silence, suffering ,beauty - but the bygone days and remembrance is the love left to carry them forward in us -this is the vow of grief

"we were near the time of our parting; and remembrance of all the bygone days sat upon us sorely"

Well, good bye .

Thank you for inviting me in to your heart. May God be our guide in it all! With love and peace- Dee