Bell Farm Reads

Happenings near and far

Every few weeks I try to highlight books, essays, and articles that I’ve enjoyed reading in the preceding months. Without further preamble, here are some recent pieces I recommend.

Death of the pastoralists: The Great Serengeti Land Grab (The Atlantic)

Shortly after writing my little essay on the tragedy of the commons, I came across this devastating article in the Atlantic about the Maasai land grab in Tanzania. The gist is that the Tanzanian state, at the behest of foreign investors wishing to develop the big game industry, forcibly removed most of the remaining semi-nomadic Maasai people from their ancestral lands. The lands have been placed under conservation, but what exactly is being conserved? It is a heartbreaking read. Unfortunately, the arc of the story is one that readers of my Substack will recognize. The state tends to see such peoples and their way of life as obstacles to conservation and/or development. The magazine has made the following extract available for preview:

It was high safari season in Tanzania, the long rains over, the grasses yellowing and dry. Land Cruisers were speeding toward the Serengeti Plain. Billionaires were flying into private hunting concessions. And at a crowded and dusty livestock market far away from all that, a man named Songoyo had decided not to hang himself, not today, and was instead pinching the skin of a sheep.

“Please!” he was saying to a potential buyer with thousands of animals to choose from on this morning. “You can see, he is so fat!”

The buyer moved on. Songoyo rubbed his eyes. He was tired. He’d spent the whole night walking, herding another man’s sheep across miles of grass and scrub and pitted roads to reach this market by opening time. He hadn’t slept. He hadn’t eaten. He’d somehow fended off an elephant with a stick. What he needed to do was sell the sheep so their owner would pay him, so he could try to start a new life now that the old one was finished.

The old life: He’d had all the things that made a person such as him rich and respected. Three wives, 14 children, a large compound with 75 cows and enough land to graze them—“such sweet land,” he would say when he could bear to think of it—and that was how things had been going until recently.

The new life: no cows, because the Tanzanian government had seized every single one of them. No compound, because the government had bulldozed it, along with hundreds of others. No land, because more and more of the finest, lushest land in northern Tanzania was being set aside for conservation, which turned out to mean for trophy hunters, and tourists on “bespoke expeditions,” and cappuccino trucks in proximity to buffalo viewing—anything and anyone except the people who had lived there since the 17th century, the pastoralists known as the Maasai.

Adam Tooze on the Green Energy Revolution (Adam Tooze’s Chartbook)

We tend to think that revolutions in energy technology make old energy sources like coal obsolete. Once new energy stock like gas, nuclear, solar, and wind become (or will become) widespread, their cost goes down–and alongside that cost our reliance on older, cheaper, dirtier energy sources diminishes. Not so, the economic historian Adam Tooze reminds us. If you examine overall energy use on a global level, what you find is instead an “accumulation and agglomeration of [all] energy sources”: in other words, more fuel sources, old and new, in use than ever before. As Tooze points out, “even the use of traditional biomass has not decline[d] in absolute terms. More poor people consume more firewood for fuel. More rich people eat meat that drives deforestation.” Based on the data available, the vision of an inevitable green energy future appears to be a consoling fiction. Part of the problem, he thinks, may be outdated conceptions of energy:

As Barak points out, part of the problem in understanding the true complexity of modernity is the very conception of “energy”. 19th-century physics defined energy as a universal force capable of being converted into different forms. It was thus fungible and universal. This conception set the stage for the stories of energy transition which both he and Fressoz expose as fragile historical constructs. Coal became the quintessential expression of that new idea of energy, allowing a mapping of the world in terms of energy flows.

That same universalized conception of coal as energy also then allowed one to imagine, coal being displaced by oil, which in turn will be displaced by nuclear power or renewables. What this ignores are the peculiar characteristics of each energy source, which means that as new sources of energy are introduced, the old are not generally discarded or simply replaced, but reconfigured and repurposed in new ways.

Side note: one of the things that interests me is the way that the physical characteristics of fuels determine energy flows and, in turn, shape our experience of the built environment. For example, oil and gas are moved through complex networks of hydraulics. Coal can be harvested, moved, stockpiled, and moved again; water energy is geographically bound to particular places. These characteristics determine the type of energy infrastructure we build and in turn our experience of the world around us. I’ve written about this elsewhere.

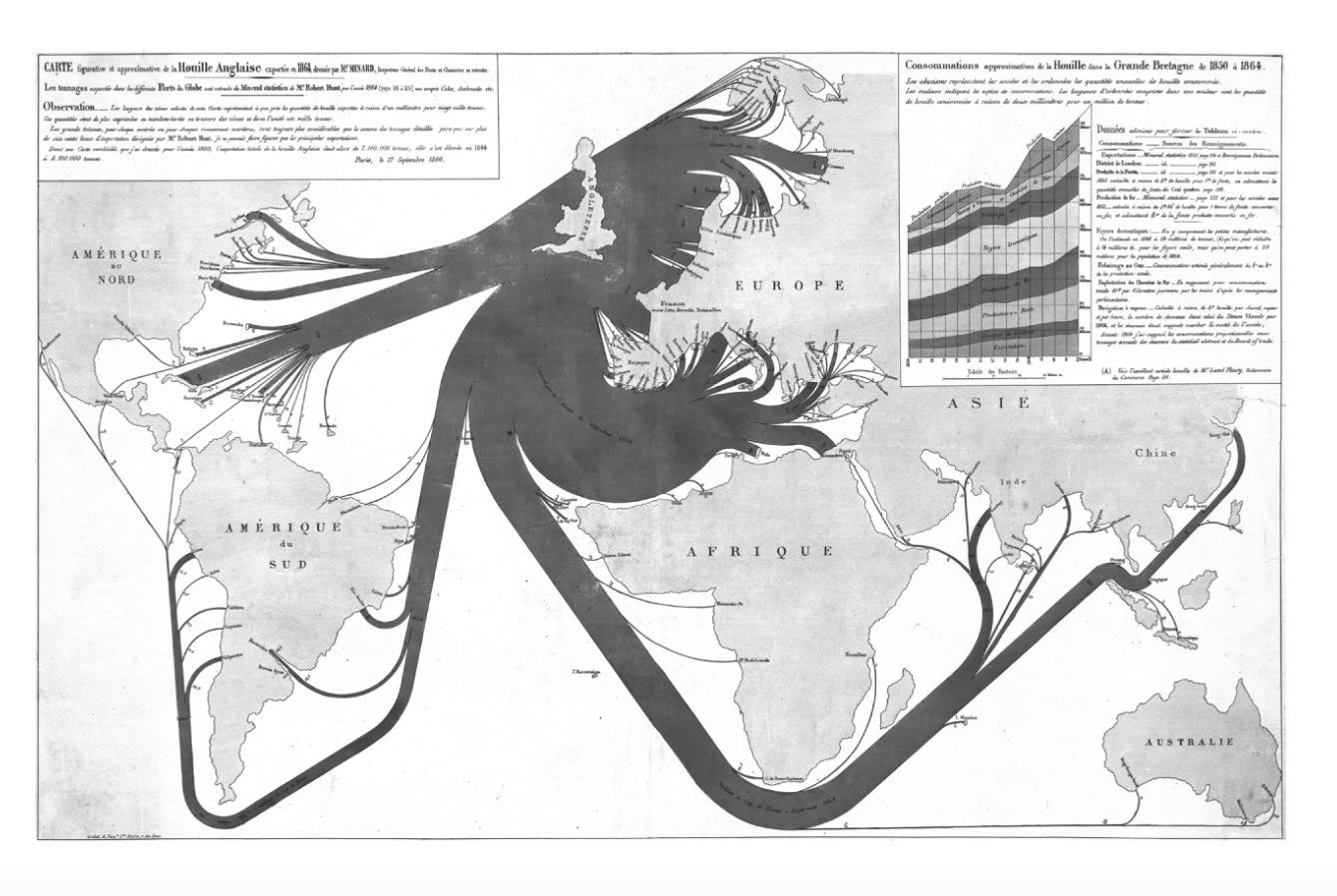

Charles Joseph Minard, British Coal Exports, 1864 (from Chartbook)

“The future was social”: Stefan Collini on Karl Polanyi’s Great Transformation (London Review of Books)

If you are interested in 20th-century economic history, consider taking a bite out of Stefan Collini’s lecture-ish review of a new edition of Karl Polanyi’s Great Transformation, a seminal study of the revolutionary changes in England’s economic circumstances in the late 18th, early 19th century. Some of Polanyi’s claims have been superseded in the historical scholarship of the last four or five decades, but concepts like the fictitious commodity still have teeth (for this reader, anyway). Well worth a read.

The Collected Letters of Emily Dickinson (New York Review of Books)

“A Letter always seemed to me like Immortality, for is it not the Mind alone, without corporeal friend?” Dickinson

On a somewhat lighter note, two scholars of Emily Dickinson have finished producing a 955-page edition of the poet’s letters. It is an amazing accomplishment many years in the making. According to Christopher Benfrey, who reviewed the edition for The New York Review of Books, Miller and Mitchell (the editors) make a convincing case for approaching the letters with the same care and attention that scholars give her poems. The best course may be to see her letter writing and poetry as continuous practices that interweave one other. “Dickinson emerges as a great writer of prose as well as poetry,” they say, “that is, a writer for whom letters in part suspend the distinction between poetry and prose.” The review is full of examples of the gnomic, terse lines that you expect to find in her poetry, like this: “You ask of my Companions. Hills-Sir-and the Sundown–and a Dog–large as myself, that my Father bought me–They are better than Beings, because they know–but do not tell–and the noise in the Pool, at noon–excels my Piano.”