Christ Among the Trades

Plus: the first edition of the Bell Farm Misc. Mailbag!

Last week, I took a look at a medieval iconographic tradition that presents Christ as a gardener. As I explained, patristic and medieval commentators were cagey about the passage in John’s gospel on which this tradition is based. Most thought Mary Magdalene must have simply mistaken Christ for a gardener. Christ wouldn’t have been caught by his followers gardening, and certainly not immediately after the resurrection. But iconography and vernacular texts sometimes took a different perspective. They did so by forcing viewers and readers to confront sensuous images of Jesus-as-gardener. In these images, Christ is presented unambiguously as someone who works the soil. This reimagining of the gospel detail provoked writers like Julian of Norwich and the author(s) of the York Corpus Christi plays to fascinating theological speculations about labor, suffering, and the common humanity our kynde shares in Christ. It also had something to say about the order of nature and salvation as well as the place of the human in the scheme of the created order.

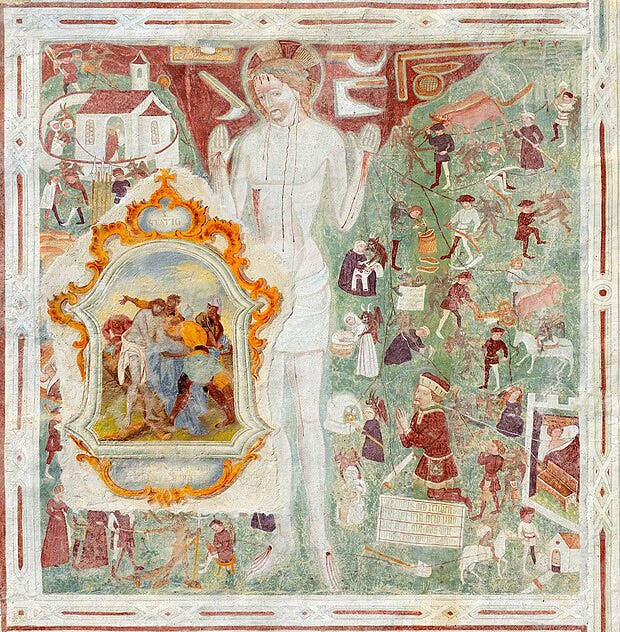

I want to begin today’s post by calling attention to a different but related iconographic tradition. It’s usually called “Christ among the trades,” because it displays an image of a suffering Christ surrounded by all kinds of tools: axes, hoes, mattocks, scales, shovels, shears, shuttles, and looms. Sometimes called Sunday Christ or St. Sunday, these wall paintings were most popular in England in the second half of the 14th century, where they decorated dozens (if not hundreds) of parish churches across rural England. By the beginning of the 17th century, nearly all of the St. Sunday wall paintings had been destroyed or covered over in whitewash. They are usually crude by modern standards, but they were clearly very important to lay people. Here’s a deluxe and well-preserved example from Italy:

Sunday Christ, ca. 1450, Urtijei, Northern Italy

Historians have disagreed about what the purpose of such icons were. The general consensus is that, by placing the tools of various trades in close proximity to Christ’s body, these icons discouraged lay people from taking up their implements and working on Sunday. In some instances, tools with points or blades appear to be directed at Christ’s bleeding flesh. If you work on Sunday, so the reasoning goes, you disobey the fourth commandment and do violence to both Christ and his church. But there is of course another way of looking at them. By simply placing the tools of the trade close to an image of the suffering Christ, the paintings dignified those tools and made labor with them theologically significant. On this reading, what you did with your hands mattered just as much as when you did it. It’s the specificity of the tools that’s so interesting to me. In one example, which has mostly faded under Reformation-era whitewash, you can clearly make out a griddle and a playing card, a six of diamonds, in the northwest corner. This photograph was taken in a parish church just east of Bury St. Edmunds. Perhaps there were card makers who belonged to the parish. Or maybe there was some guild or other trade association whose symbol was the six of diamonds. Either way, such images suggest that the trades find their proper home in the church, alongside Christ. Labor–gardening as well as blacksmithing, weaving cloth or kneading dough–belongs to the travayle humans share with Jesus.

I don’t think a view like this excludes sabbatarianism. While sacralizing certain forms of skilled labor, such paintings could still discourage people from working on Sunday. What’s significant to me, though, is that ordinary people saw their labor with the material world as continuous with, and completed by, the spiritual work of the church. Here is a world in which the material and the spiritual were deeply interwoven and interdependent. Labor, nature, spirituality, and art weren’t (could they have been?) siloed domains.

Here’s another example. Consider Eamon Duffy’s description of parish life in pre-Reformation Morebath, a tiny village in Cornwall. Most of the villagers who lived there made their money from small to midsize sheep flocks that they tended on common land or waste. The parish church also owned a flock of sheep (in addition to several hives of bees), which helped defray the cost of various liturgical items like vestments, reliquaries, and statues. (Duffy relates one instance in which a widow has her husband’s wedding ring melted down into a pair of tiny golden shoes for a statuette in the church.) On feast days, they would sometimes eat the animals. Duffy mentions one instance when a lamb that belonged to the parish accidentally bled to death after castration. It was eaten by the community on an ale day soon after. What’s most interesting about this arrangement was that it was the common responsibility of the members of the parish to care for the sheep. Here’s Duffy’s account of how it worked:

Every parish which drew income from livestock must have kept records of where the animals were lodged, and lists of parishioners with the number of animals in their keeping are a feature of other parish accounts of the period…The Morebath church sheep were distributed, in principle, one to a household. If a ewe had a lamb in the course of the year, the lamb was passed as soon as it was weaned to another parishioner, so that no one should be burdened with more than the statutory single animal from a given store, though some parishioners might have sheep from more than one store. Surplus sheep for which a custodian could not be found were taken to the village pound and sold. This meant that in a given year, two thirds or more of the households in the parish had at least one of the church sheep, and young animals were being passed from one farm to another in the course of the year, as parishioners and wardens tried to spread the burden of responsibility fairly. The sheep counts were…the most concrete expression of the demands which the parish made on the parishioners of Morebath, and of their mutual obligations… (41)

In Tudor Morebath, Duffy explains, “the spiritual and the material intertwined so tightly” that it was impossible to find where one domain ended and the other began (109). When western England erupted in revolt in the summer of 1549 (the so-called Prayer Book Rebellion), the rebels were objecting to conformity in spiritual matters (like worship in the English language) as much as they were to material and economic ones, like the controversial poll tax on sheep. The region was famous for its “kersey,” or woollen cloth that had ribs in it. The production of Devonshire wool had become so important to the crown’s revenue that it was one of the earliest counties in England to be enclosed. By the eighteenth century, there was very little waste or common left. Small producers–and communities like Morebath–had mostly disappeared.

Okay. That’s enough about the Middle Ages for now. On to your questions and comments.

THE BELL FARM MISCELLANEOUS MAILBAG

Many of you were curious about my use of the Vulgate and the Douay-Rheims translation of the Bible. It’s for historical reasons. Typically, if I reference something in the Bible, I will use the NRSV (New Revised Standard Version); unless you’re working with the Greek or Hebrew text, that’s fairly standard academic practice. But if I’m dealing with something from the Middle Ages–and a text in Latin, particularly–I’ll turn to the Vulgate ,Jerome’s monumental translation of the Hebrew Bible and New Testament (4th century), or to the 19th-century translation of the Vulgate into English that is referred to as the Douay-Rheims Bible. The Vulgate was the translation of the Bible that was used by the Roman Catholic Church until 1979. The Douay-Rheims gets you really close to a literal translation of the Vulgate. And for all Jerome’s erudition, the Vulgate is, as far as translations go, inaccurate in places and not particularly well written. (In Confessions, Augustine implies that it was so poorly written that it kept him from joining the church (3.5.9).)

I got a really interesting email from Will, a scholar of the Hebrew Bible, about my essay on Jesus the gardener. Here is what he says:

I could not help but think of the garden in Genesis 2–3 as I read your discussion of the Magdalene cult and John 20:15. You do mention this text when discussing Julian's Revelations, but I think it's worth pointing out just how well this text fits the patterns you note in your essay. The story's plot unfolds from the basic problem that the earth isn't growing anything. It is well-watered but uncultivated — perhaps there's a nod here to the irrigation canals used to farm the alluvial plains of ancient Mesopotamia. God solves this problem by creating a human to tend and till the garden. The term used for God forming (wayyı̂ṣer) the human from the earth is that of a potter shaping clay at the wheel, and both a potter and a gardener work with their hands in wet soil. Even though the human is delegated the work of keeping up the garden, God also appears like a gardener in this text, planting the garden in the first place (2:8) and growing trees for both their beauty and their provisions for food (2:9). We could also speculate about the human pair hearing God "walking in the garden at the time of the evening breeze" (3:8). Do they hear God's heavy footsteps, or perhaps the sound of a gardener moving about, working at a cooler, more pleasant time of day? We're left to wonder because the text doesn't say, but it is clear that God is on the ground in the garden together with living things. Of course, the idyllic setting of the garden gives way to the toil of farming culture (3:17–19), but the garden of Eden is held up as a hopeful sign for human interaction with the land in Isaiah 51:3, where human flourishing is deeply connected to that of the land as well. This kind of hopeful interpretation of the story leads into the idea of "cosmic gardening" you mention in the essay. If the first Adam was made because "there was no one to till the ground" (2:5b) then it would make perfectly good sense that the Second Adam would continue this work.

And lastly, a fascinating note from Alex, a computer scientist. He was intrigued by my essay on Weil’s Abolition of All Political Parties. Here’s what he had to say:

there’s a nice mathematical formalism that could be used to model the claims about individual passions vs. universal truth, as well as the effect of political parties and other forms of mass persuasion. the basic idea is related to signal theory:

imagine a group of individuals who receive information that consists of a true signal plus superimposed random noise. if you add up everyone’s received information (or average it), then the true signal will emerge because the random noise will tend to cancel out. but this is only true if the noise is random and uncorrelated across individuals. if the superimposed noise is correlated across individuals (i.e., they tend to get the same noise, perhaps from a common source of noise or distortion), then the canceling out won’t happen, and the average will not be the true signal, but that signal distorted by the correlated noise.

Sit with that one a bit. Think it would work? In the real world, is there a way to eliminate “superimposed noise” correlated across individuals? Feel free to weigh in on the comments and let me know.