Field Notes: Passionflower

Passiflora incarnata

Summer pasture holds many secrets. Hidden rabbit warrens explode with activity when you happen to walk across one. If you stop and peer down into the crown of thick grass, you might find a nest of killdeer eggs that looks abandoned until you hear the familiar cry of the mother, who is circling above and has been watching you. Then there are the wildflowers that like to creep and hug the ground instead of shouting their colors in your face.

None of these hidden creatures are more welcome to the farm’s human inhabitants than the arrival of the fruit of the native passionflower (Passiflora incarnata). Like many plants that have a wide geographic distribution, passionflower goes by many names. Maypop, purple passionflower, passion vine, apricot vine—whatever you want to call it, the vine produces clusters of delicious, egg-shaped fruit in mid-September. As the fruit ripens, it produces juicy, white seed pods behind a shiny green shell. The taste is similar to the plant’s more well-known cousins, Passiflora edulis (purple passionfruit) and Passiflora granadilla: tart and refreshing. I have tried these, and this one tastes wilder somehow: bracing, tropical, earthy, quickening.

The flower of Passiflora incarnata.

There are two reasons native passionfruit is a secret. Not many people know about it, and (because?) it is so damn hard to find. The fruit pods and leaves are a shade of green that is nearly indistinguishable from the greens of grasses and legumes that it tends to grow on top of. A few weeks ago, I stood in our pastures among many passionfruit vines, scanning the ground for fruit. I wasn’t able to see them until I got down on my hands and knees and turned my head sideways so I could look underneath the vine’s shady leaves. Sometimes you have to put your hands on the vine itself and follow it and hope you come across something that a deer or a rabbit hasn’t mangled. Children are more skilled and patient with this method, and they are usually willing to help if you promise they can keep some of what they find. Here’s another way you might discover them: if you step on one and hear the classic “pop” of the shell cracking, you know you are among the maypops, or at least one ruined maypop.

The fruit’s elusiveness is not because the vine has failed to make itself known. In July, passionflower produces the most delusionally beautiful blossoms: spiky, three-dimensional towers of lavender (or sometimes white) petals, squiggly purple filaments, and five yellow anthers on top that actually look like antlers. When passionflower is in bloom, you can spot the flowers from many yards away. But unless you flag the spot of ground where you saw the flowers, you’ll be hard-pressed to find them three months later, when the blossoms are long gone and the fruit is ripening.

A shirt full of maypops.

The Latin for maypop is Passiflora incarnata. It means something like “incarnated flower of suffering.” Carl Linnaeus, the founder of the binomial system still used to categorize all living things, named the plant himself. He chose a name that tried to pay homage to the first Europeans, Jesuit missionaries, who found this remarkable vine in their journeys to the Americas. Sometimes the Jesuits called the vine granadilla, “little pomegranate.” More often, they called it the flos passionis, the flower of the Passion, or the flower of suffering.

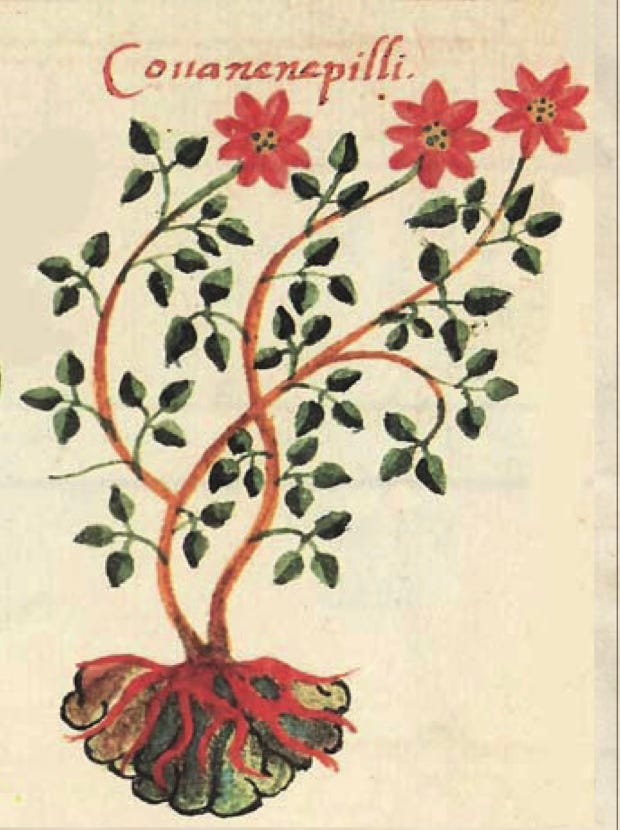

An image of a passiflora species first shows up in the famous Codex Badianus, an herbal formulary complied by some of the earliest Spanish missionaries to Mexico. The codex contains beautiful, hand-painted images of the medicinal plants the Aztec people cherished and how they used them. The authors of the codex note that passionflower (coanenepilli in Aztec) is good for reviving prisoners who have been handled too harshly. By 1580, it is supposedly being cultivated in the gardens of the the Spanish king Philip II. From here on out, Passiflora sp. show up frequently in Jesuit herbal and botanical manuals, and with increasingly fantastic proportions.

A drawing of what is probably a Passiflora sp. from the Codex Badianus, 16th cent.

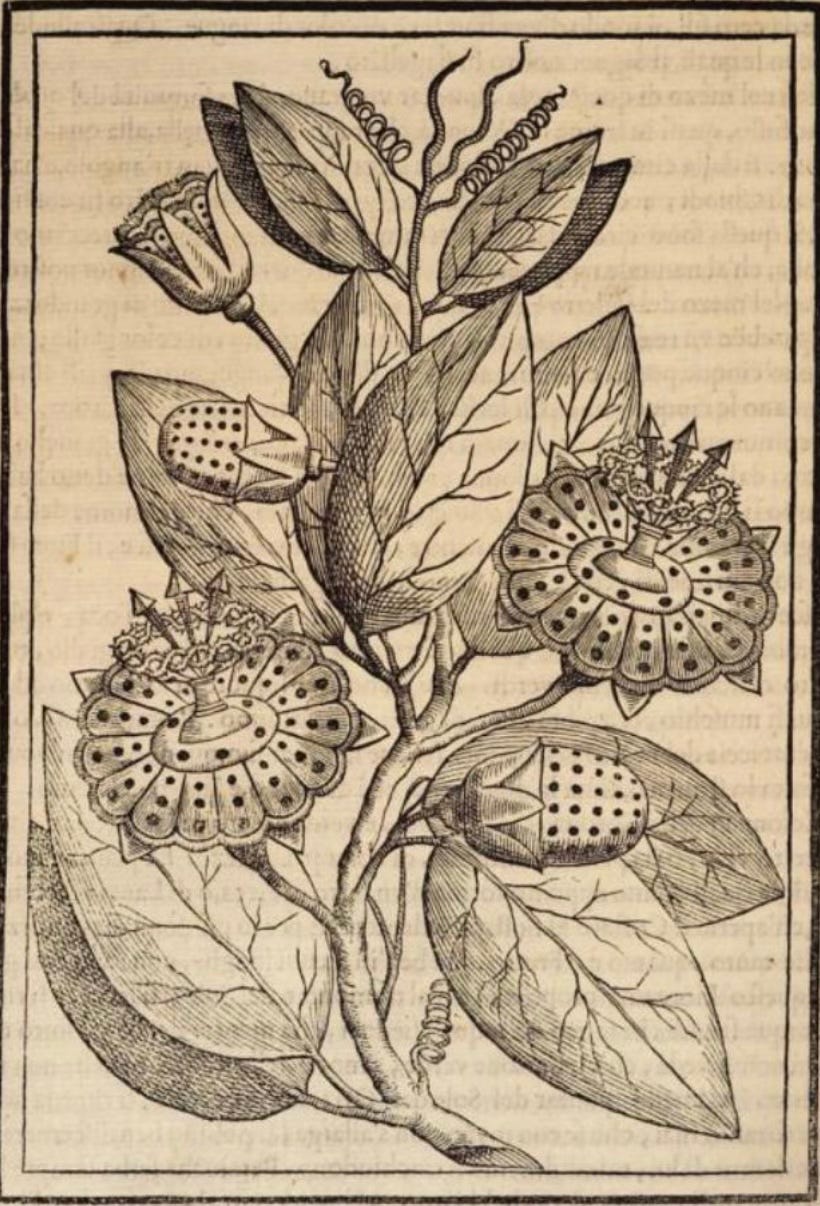

Here is an image of flos passionis that circulated widely in Europe in the early 1600’s: a tall, faintly Greek pedestal is set upon a circular platform with polka dots lining the rim. The pedestal props up three sharp swords that jut up and outward towards the viewer. The swords are encircled by what looks like a crown of thorns. Nicolas Monardes, a Spanish doctor who compiled “Ioyfull newes out of the newfound world” [trans. English, 1577], was the first to connect in print the appearance of the passionflower to the Passion of Jesus. This strange vine “casteth a flower like to a white rose, and in the leaves it hath figures which are signes of the passion of our Lorde, that it seemeth as though they were paynted with muche care, where the flower is more particular than any other that hath beene seene.”

Later commentators were less restrained. Antonio de Leon Pinelo [1589–1660], a historian who trained with the Jesuits in Lima, insisted throughout his career that the original garden of Eden was located somewhere in his native Peru. What fruit might have tempted Eve, if not the fruit of the flos passionis? Never mind that passionflower is a vine, and not a tree. Here is a sign of the felix culpa: the remedy and the curse contained within the morphology of the plant itself. How fitting that the fruit of the flower of the Passion should serve as the object of Eve’s first sin. Giacomo Bosio, an Italian member of the Knights Hospitaller (a Catholic military order based in Malta), goes even further in his apology on behalf of “The Triumphant and Glorious Cross” [Triomphante e gloriose croce, Rome, 1609]. After discussing the Christological significance of the unicorn, Bosio turns to the passionflower. He claims that the Spanish call the vine “la flor de las cinco llagas [wounds]”, because its flower displays in detail all the traditional symbols of Christ’s passion. The five anthers on top are the five wounds of Christ (two in the hands, two in the feet and one in the side); the tendrils are the whips the Roman soldiers used to beat him; the three stigmas are the three nails; the “crown” of filaments are the crown of thorns; and the five petals and five sepals point to the ten disciples who remained faithful to him (Judas and Peter, of course, go missing). How marvelous and strange, Bosio says, that God would hide the mystery of his Passion in plain sight of so many ignorant and impious heathens who had no clue what they were looking at.

from Bosio’s Triomphante e gloriose croce [Rome, 1609], Libro secundo, p. 164.

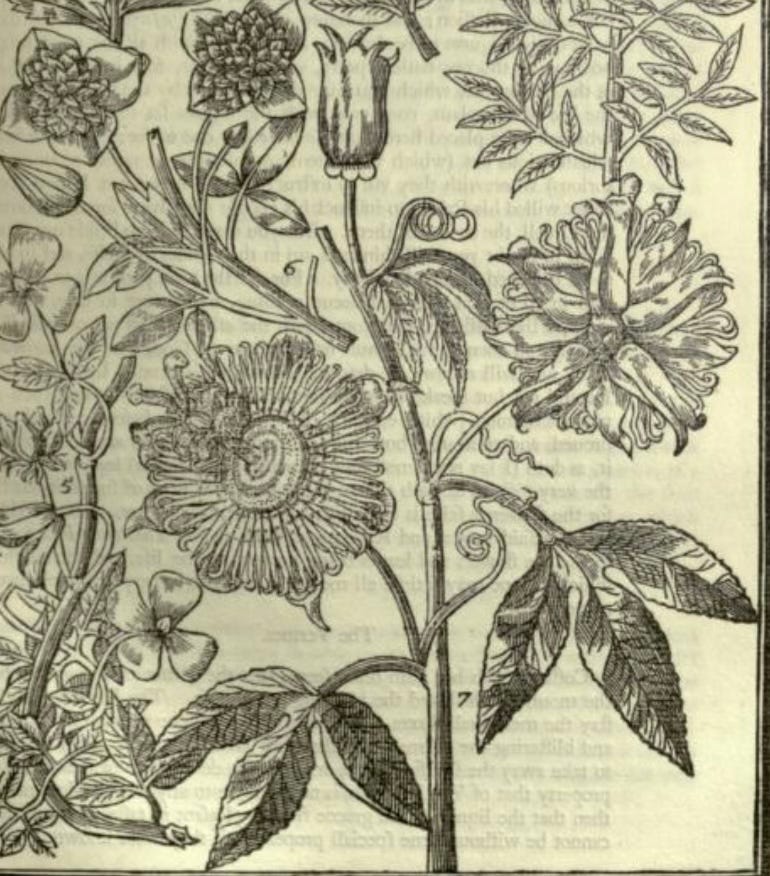

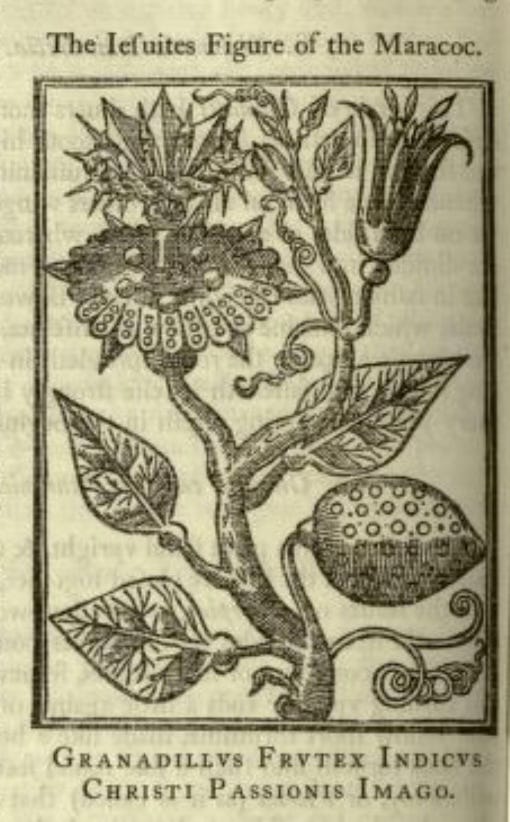

Protestant botanists had none of this. Using a plant to teach doctrine was one thing. Suggesting that God had placed an icon of the most powerful devotional object of the Counter Reformation in the middle of a pagan paradise was something else. For John Parkinson, an English apothecary and the royal botanist of Charles I, the worst was that it encouraged botanical misdescription—“lyes” “from the Divell,” as he put it in Paradisi in sole paradisus terrestris [London, 1629] (The Latin title is confusing because it puns on Parkinson’s name: “park-in-sun’s terrestrial park”). In his discussion of the “virtues” of the passionflower, Parkinson incorrectly identifies the vine as a species of clematis before letting his readers know that the English have taken to calling it the “Virgin or Virginian Climer,” because it is a vine first discovered and sent back to England by an agent of the Virginia Company (probably John Smith). The Virginians call it “maracoc,” after the custom of the Powhatan people. Spaniards of the West Indies call it granadillo. Still others, after the manner of “some superstitious Jesuite” (he won’t even mention the name!),

would faine make men beleeve, that in the flower of this plant are to be seene all the markes of our Saviours Passion; and therefore call it Flos Passionis: and to that end have caused figures to be drawne, and printed, with all the parts proportioned out, as thornes, nailes, speare, whippe, pillar, &c. in it, and all as true as the Sea burnes which you may well perceive by the true figure, taken to the life of the plant, compared with the figures set forth by the Jesuites, which I have placed here likewise for every one to see: but these by their advantagious lies (which with them are tolerable, or rather pious and meritorious) wherewith they use to instruct their people; but I dare say, God never willed his Priests to instruct his people with lyes: for they come from the Divell, the author of them.

“As true as the Sea burnes”: this Jesuitical fiction, reproduced faithfully from Bosio’s text, lies on the page opposite Parkinson’s own meticulous rendering. He’s certainly got a point. Parkinson’s drawing is impressively accurate. The “lye” is plain for all to see. Let the reader understand, etc.

Parkinson’s drawing of Passionflower incarnata, Paradisi in sole Paradisus terrestris (London, 1629), p. 395. Below, his reproduction of the image from Bosio’s text.

It’s strange to look out in your pasture and find a plant that holds such a modest yet vexing place in Western history—a plant that, through no fault of its own, absorbs and reflects back to us our own histories of colonization, the extermination of indigenous peoples, doctrinal disputes between Protestants and Catholics. Once you see it, it’s hard to unsee. Passionflower, indeed. In a book on the philosophy of plant life, Michael Marder suggests that the sheer exposure of plants—their rootedness to a single place; their horizontal, chlorophyllic embrace of sun and sky—is the key to understanding their relationship to other living things. Plants always go before animals, so to speak, creating the atmospheric and metabolic conditions that make other lives possible. Plants therefore signify a “primordial generosity” that precedes and encompasses the animal. But exposure is also what sometimes tempts us into thinking that they are pure passive—as if plants were simply waiting around for someone (or something) to take them away.

Over the course of September, the kids and I collected about a hundred passion fruit from the farm. We devoured them almost as quickly as we could pick them. Before long, the deer found them, and then the sheep, and then the cows. It is the middle of October now, and all the maypops and maracocks have gone. They are a short-lived fruit; you have a very narrow window to catch them before they go bad or go missing. The vines have gone, too. Evidently the animals found them tasty. Passionflower will be back next year, though, in new and surprising places. Ever since we stopped clipping pasture, we find it somewhere every year. In gobbling up the fruit we do our part—the animal part—spitting out the pips as we make our way back to the house or to the next job.