Field Notes: Vetch and Vavilov

Weeds, biomimicry, and the changing of the seasons.

Early summer is the time of year when the blooms of one of my favorite spring weeds, hairy vetch (Vicia villosa), begin to disappear. From late March to the end of May, its long clusters of purple flowers drape across the stalks of perennial grasses like fescue and orchardgrass. By mid-June, the flowers are replaced with the plant’s dark, skinny seed pods that look like cow’s horns.

hairy (villosa) vetch in our pastures.

To some gardeners, vetch is a menace. It has a tendency to take over where there isn’t much diversity in the grasses, and its seeds remain viable in the soil for a long time. In some states, hairy vetch and its cousin, cow vetch (Vicia cracca), are considered invasive species. That’s a bit of a shame, because vetches behave well in perennial grassland ecosystems where there is built-in competition with other species.

But I love vetch. It’s a tremendously nutritious forage for sheep and cattle. It’s also a legume, which means that it hosts colonies of nitrogen-fixing bacteria called rhizobia that live in the nodules of its roots. The plant will take up the nitrogen these bacteria produce (NH3) and use it for its own growth and development. For this reason, it makes a great “chop and drop” cover crop in the garden: the nitrogen in the vetch plant’s roots remains in the soil after the plants been chopped up.

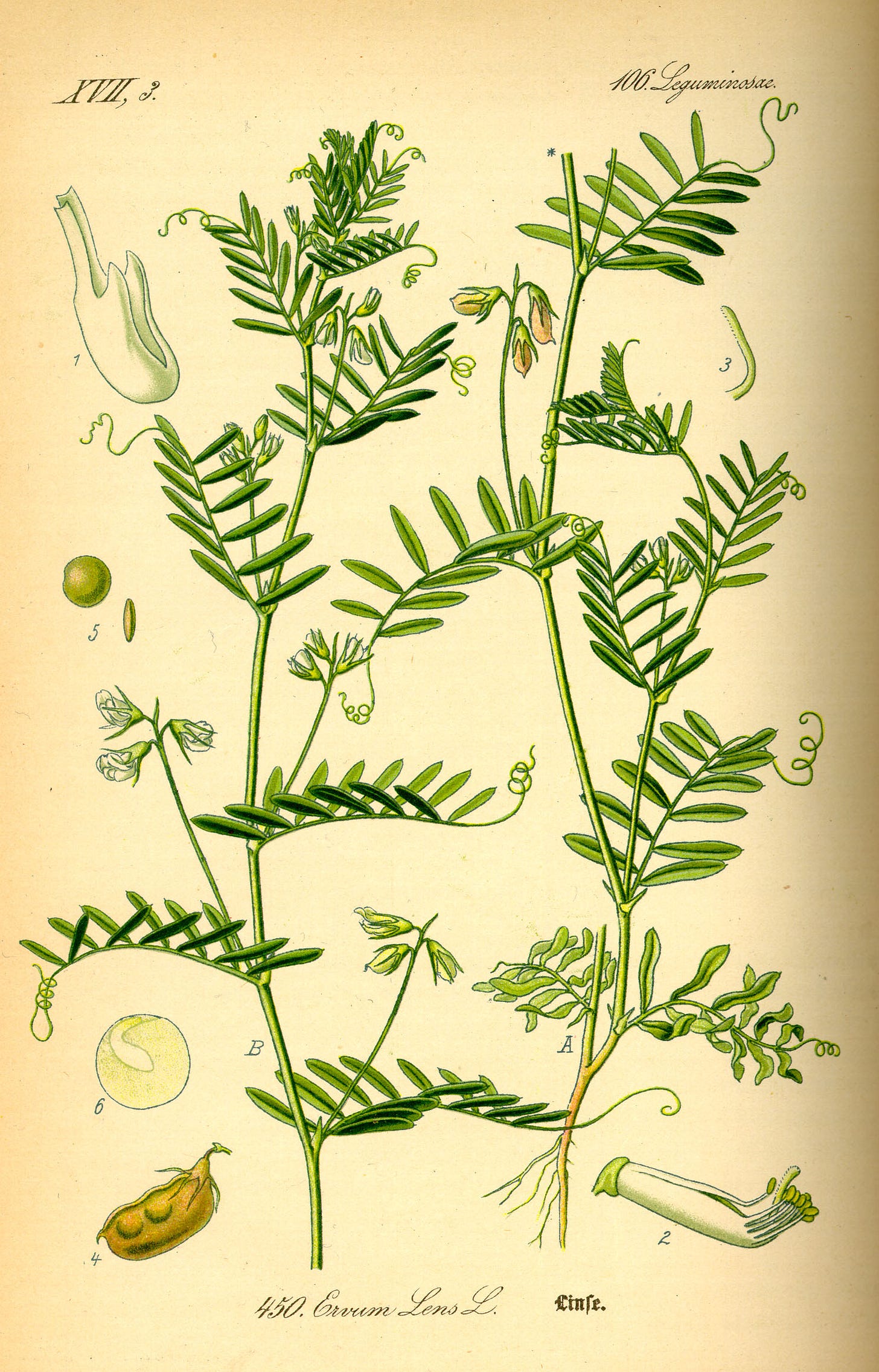

Lens culinaris, or: the lentil.

Vetches have an interesting evolutionary history, too. Common vetch (Vicia sativa) is as old as agriculture. It developed in the grain fields of the Near East, where it was difficult to tell the plant apart from a very old and important domesticated crop: the lentil (Lens culinaris). But vetch’s seeds were originally round, so all a farmer had to do was wait until the plants formed seed pods and then sort the crop. Over time, though, vetch evolved to make its seeds flatter and flatter, until it became very difficult to tell the plants apart at all. Farmers inevitably harvested vetch seeds with the lentils, and soon both plants spread throughout the Mediterranean.

As Stefano Mancuso explains, this form of mimicry is called Vavilovian mimicry, after the Russian agronomist Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov, who first studied it. Vavilov described it as a consequence of artificial selection: it is humans, not natural systems, who are driving the evolutionary change through the selection of specific features in plants. Vetch adapted to selection pressure by producing thinner and thinner seeds that became indistinguishable from lentils. Cereal rye (Secale cereale) is another example of Vavilovian mimicry; originally it was a wild grass that grew in wheat and barley fields.

Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov, botanist, killed in Stalin’s purges.

But far less desirable plants have emerged through the mechanism of Vavilovian mimicry. Consider herbicide-resistant plants like Amaranthus palmeri, an edible cereal grain that is native to North America, mind you, but a plant that most farmers hate because it competes with commodity grain. The “enormous chemical pressure” (glyphosate) we’ve exerted on weeds like Amaranthus has given rise to variants that have adapted and now cannot be killed by any amount of chemical herbicides. At a time when global commodity yields appear to have hit their ceiling (we simply cannot get more per acre in the industrialized world than we are currently getting, and those numbers are in decline in North America, Europe, and Australia), herbicide-resistant variants are increasingly being found all over the world. That’s bad news.

Vavilov was on the first scientists to advocate for a global seed vault to protect the genetic diversity of plants from human interference. We’ve heeded that advice, in part, through the development of the Global Seed Vault at Svalbard. But until we learn and re-learn how to farm with nature rather than against it, we’ll be fighting the same battles.

It is great to find another substack with a similar ethos to mine (our substack intro lines are almost identical!)

You got my attention with your phrase 'my favourite weed' - it is not every day that you find a farmer conversing about their 'favourite' weed! It is interesting isn't it what plants we call weeds and how this influences how we treat them compared to say if we called them a wildflower. With a weed, without a second thought we apply pesticide (or for the organically minded, pull it up) but to apply pesticide to a wildflower almost seems sacrilegious. However to different people (e.g. the farmer bs the botanist) both descriptors could apply to the same plant. Thus our act of naming holds immense significance.