Happy New Year!

I’m writing to wish you all a happy New Year from Bell Farm. For the last month, our house has been a blur of bustle and holiday activity: moving in, unpacking, celebrating Christmas, and getting our kids settled into what feels to them like a very different home than the one they used to live in. No matter how many items we tick off, the parents’ list of oddjobs never seems to diminish. But I am pleased to report that we are moved in, deo gratias, and more or less unpacked. And while there is still plenty left to do, especially on the exterior of the house, much of it will wait until the weather turns warmer. Here we are, then, having crossed over into January, sliding back into the rhythms of church and farm work.

Lots more writing is passing through the pipeline in the coming months. Please stay tuned. In addition to an essay coming out in the journal Comment next month (I hope), I’ll be debuting a series of essays here on the Substack. Next Monday, January 8th, the first installment will drop. It begins in a meandering sort of way with an experimental novel by Thomas Hardy called The Woodlanders (1887). From there, I open a series of reflections on the expropriation of rural communities and ask what sorts of possibilities there might be for reimagining connections between the country and the city. My goal is to publish one long essay per month here and then have three additional posts per month on topical subjects: plants, poetry, ideas, etc. Goodie is hard at work on an essay that describes what it’s like to keep a milk cow. I’m excited to see what she turns up. If you want to support our work, please consider contributing to the cause.

For now, though, I will leave you with an excerpt from Hardy, whose prose style I fell in love with this fall. In October I reread Raymond Williams’ The Country and the City, and it made me want to pick up some of Hardy’s novels I hadn’t already read. I had forgotten how shockingly precise and compact his style is–“pictorially gnomic,” James Woods writes, in this LRB review essay. Disinclined to use metaphor, Hardy always seems in search of what Flaubert called le mot juste–the right word, the word that can do justice to the thing.

If you don’t know who or what I’m talking about, Thomas Hardy was a Victorian novelist who was born in a village of Dorchester, England. After schooling, he worked as a successful architect for a number of years before quitting his job and moving back to the country, where he became a celebrated writer. The passage I’ve chosen comes from a different novel than the one I mentioned. This one is called The Return of the Native (1878), and it opens with a wintry description of a place called Egdon Heath. Egdon Heath is a common waste that sits in the middle of Hardy’s fictional universe called Wessex. If you read the essay I published in Plough last year, you’ll know that I have an abiding interest in lands that are (or were) legally waste land. Not many tracts of its kind remain in England, Hardy says; its physiognomy points back to a geological timescale that endures in surprising and elusive ways. “It could best be felt when it could not clearly be seen”: so says Hardy of Egdon. Enjoy.

A Saturday afternoon in November was approaching the time of twilight, and the vast tract of unenclosed wild known as Egdon Heath embrowned itself moment by moment. Overhead the hollow stretch of whitish cloud shutting out the sky was as a tent which had the whole heath for its floor.

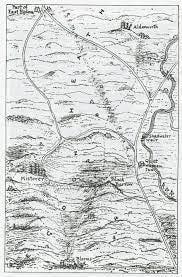

Hardy’s hand-drawn map of Egdon Heath.

The heaven being spread with this pallid screen, the earth with the darkest vegetation, their meeting-line at the horizon was clearly marked. In such contrast the heath wore the appearance of an installment of night which had taken up its place before its astronomical hour was come: darkness had to a great extent arrived hereon while day stood distinct in the sky. Looking upwards, a furze-cutter would have been inclined to continue work: looking down, he would have decided to finish his faggot and go home. The distant rims of the world and of the firmament seemed to be a division in time no less than a division in matter. The face of the heath by its mere complexion added half-an-hour to eve: it could in like manner retard the dawn, sadden noon, anticipate the frowning of storms scarcely generated, and intensify the opacity of a moonless midnight to a cause of shaking and dread.

In fact, precisely at this transitional point of its nightly roll into darkness the great and particular glory of the Egdon waste began, and nobody could be said to understand the heath who had not been there at such a time. It could best be felt when it could not clearly be seen. Its complete effect and explanation lay in this and the succeeding hours before the next dawn: then and only then did it tell its true tale. The spot was, indeed, a near relation of night; and when night showed itself, an apparent tendency to gravitate together could be perceived in its shades and the scene. The sombre stretch of rounds and hollows seemed to rise and meet the evening gloom in pure sympathy, the earth exhaling darkness as rapidly as the heavens precipitated it. The obscurity in the air and the obscurity in the land closed together in a black fraternization towards which each advanced half way.

The place became full of a watchful intentness now. When other things sank brooding to sleep the heath appeared slowly to awake and listen. Every night its Titanic form seemed to await something; but it had waited thus, unmoved, during so many centuries, through the crises of so many things, that it could only be imagined to await one last crisis–the final Overthrow.

****

Civilization was [the heath’s] enemy. Ever since the beginning of vegetation its soil had worn the same antique brown dress, the natural and invariable garment of the formation. In its venerable one coat lay a certain vein of satire on human vanity in clothes. A person on a hearth in raiment of modern cut and colours wears more or less an anomalous look. We seem to want the oldest and simplest human clothing where the clothing of the earth is so primitive.

To recline on a stump of thorn in the central valley of Egdon, between afternoon and night as now, where the eye could reach nothing of the world outside the summits and shoulders of heathland which filled the whole circumference of its glance, and to know that everything around and underneath had been from prehistoric times as unaltered as the stars overhead, gave ballast to the mind adrift on change, and harassed by the irrepressible New. The great inviolate place had an ancient permanence which the sea cannot claim. Who can say of a particular sea that it is old? Distilled by the sun, kneaded by the moon, it is renewed in a year, in a day, or in an hour. The sea changed, the fields changed, the rivers, the villages, and the people changed, yet Egdon remained. Those surfaces were neither so steep as to be destructible by weather, nor so flat as to be the victims of floods and deposits. With the exception of an aged highway, and a still more aged barrow [an ancient burial site] presently to be referred to–themselves almost crystallized to natural products by long continuance–even the trifling irregularities were not caused by pickaxe, plough, or spade, but remained as the very finger-touches of the last geological age.

The above mentioned highway traversed in a curved line the lower levels of the heath, from one horizon to another. In many portions of its course it overlaid the old vicinal way, which branched from the great Western road of the Romans, the Via Iceniana, or Ikenild Street, hard by. On the evening under consideration it would have been noticed that, though the gloom had increased sufficiently to confuse the minor features of the heath, the white surface of the road remained almost as clear as ever.