On the Abolition of All Political Parties

A curious essay from Weil

Political parties are a marvelous mechanism which, on the national scale, ensures that not a single mind can attend to the effort of perceiving, in public affairs, what is good, what is just, what is true. As a result–except for a very small number of fortuitous coincidences–nothing is decided, nothing is executed, but measures that run contrary to the public interest, to justice and to truth. Simone Weil, “On the Abolition of All Political Parties”

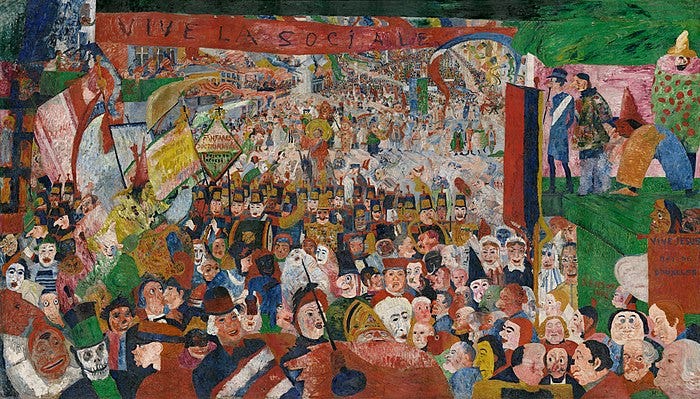

Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889, James Ensor, oil on canvas, 1888, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Life has been full on Bell Farm. Last week, Goodie started a new job. She’s now the Senior Pastor at Blacknall Memorial Presbyterian Church in Durham, North Carolina. While both of us were able to take some time away to plan and strategize for the transition, the truth of the matter is that we’ve been without consistent childcare since the beginning of summer. It’s been hard to predict where we will find time for writing and reflection, much less time for the work of running a farm and co-laboring in the household. Help is on its way–it arrives Monday, in fact–but the family has not yet gotten into a rhythm yet, which means that the miscellany has been updated infrequently. The plan is to get weekly posts going again next week.

There was a presidential debate last week. If you made the mistake of tuning in like I did, allow me to offer a purgative: Simone’s Weil’s short essay, On the Abolition of Political Parties, first published in 1943. After Tuesday night, the proposal embedded in the essay’s title seems eminently reasonable. Ten years ago, NYRB Classics republished Weil’s full text and included an excellent introductory essay by the Polish poet and Soviet émigré, Czeslaw Milosz. Order a copy. For now, you can find an online version here.

Many of Weil’s political essays include specific but rather draconian proposals for the reordering of society. On the Abolition of Political Parties is no different. In the essay, Weil is so supremely confident in the good that banishing political parties will do that, in the course of parsing out her arguments, you begin to wonder whether there will be any politics left when all the parties are gone. Her vision of a democratic society is one in which the people vote directly for candidates who “associate and disassociate [with one another] following the natural and changing flow of affinities” (29). The fluidity of political affinity stems from the nature of public discussion about truth, justice, and the public interest. For Weil, the organs of political thought would be journals that the people would support and maintain. It turns out that such an arrangement would involve quite a bit of censorship. Weil says that mendacity, which inevitably leads to collective delusion, is the enemy of democracy. But she never indicates who would be doing the censoring or what authority the people would arrogate in order to do so (30).

Still, albeit brief, Weil’s analysis of the modern political party is trenchant. Drawing on Rousseau’s concept of the general will (volonté générale) in The Social Contract [1762], Weil argues that a democratic society is just if and only if the will of the people conforms to justice (5-6). A democracy isn’t an end in itself. Only if it enables people to desire and actually pursue truth, justice, and the public interest more effectively than other forms of government is democracy to be preferred. According to Weil, Rousseau sketched a picture for how democracy might achieve this. In a functioning democracy, individual passion and private interest have a tendency to cancel each other out. The idea is that, as I express a passion or my own private interest and you express yours, they act as counterweights against each other. But unlike passion and private interest, reason is universal. Therefore, when “everyone thinks alone and then expresses his opinion” about a common issue, these opinions will “most probably” “coincide inasmuch as they are just and reasonable” (6). What remains after such sifting of passons and reasons are common interests, or what Weil describes as a “universal consensus” that “may point to the truth” (6).

The problem, Weil thinks, is that democracies are frequently vulnerable to collective passion–“an infinitely more powerful compulsion to crime and mendacity” than the passion of an individual (8). When the will of the people is captured by a vision of justice that is distorted, partial, or incomplete, it ceases to be legitimate. Nothing short of goodness itself is the proper object of the will. When a collective passion takes root, the people clash with “infernal noise,” and “the fragile voices of justice and truth are drowned” (9). Thus, Rousseau’s thesis of equilibrium–individual passions balance each other; the general will moves society closer to the truth–this balance is reversed. When the people are deluded, the general will is a “caricature” of truth and an individual’s expression of justice more likely to be closer to the truth than the will of the people (9).

Political parties are machines for collective passion. They trade in partial or particular visions of the public good–the good of one social or racial group; of a class or a corporate interest; of an ideology or a creed. They have no interest in free and open debate about what constitutes goodness or justice. Instead, they indoctrinate their members with specific policies, proposals, and platforms that are distortions. And they are at least implicitly totalitarian in their structure: no amount of power is ever enough to satisfy the leaders of a party. In any major political party, communist or conservative, socialist or otherwise, “the quest for total power becomes an absolute need” because the party’s platform is almost always devoid of vision–and “what is utterly devoid of existence cannot possibly encounter any form of limitation” (14).

Read on here.