A Brief Case Against the Novel

A brief theory of why most novels suck, and why some don't

Salon d’Or [Hamburg, 1871], William Powell Frith, oil on canvas.

1

Not that long ago, I didn’t read novels unless I had to. When I did reach for one, I wouldn’t have gone looking for something written in recent memory. It’s difficult to remember how I got this way, but I’m fairly sure the aversion stemmed from growing up where I did in the South. In junior and high school, I felt obligated to read everything William Faulkner wrote, and even though I came close (never got to A Soldier’s Pay [1926]!), I always found myself drawn to other, seemingly more modest works of fiction. The short stories of Leo Tolstoy, Flannery O’Connor, and Nathaniel Hawthorne stick out in memory. The totalizing gaze of a book like The Sound and the Fury [1929], working so relentlessly through the thought-worlds of four damaged people–formally, anyway, a novel like this seemed too deeply implicated in the racism it was seeking to describe to be anything close to redeemable. Or at least not emulated, and certainly not now. For all its formal innovation and influence, Faulkner’s work never indicated that the South could be anything other than it was. It felt to me like a demonic amount of energy to invest in representing a world that desperately needed to be dismantled and destroyed.

Although I didn’t have the language for it, it seemed to me that the other, more modest works I loved were in the business of making art of a different kind. I remember coming away from Tolstoy’s short stories feeling like they burned with a weird intensity: this could have been about me, or about people I knew (“The Devil,” posthumously published, was a favorite). And who knows; maybe I was onto something. My fondness for Tolstoy has only grown as the years go by. For all its reliance on the conventions of the 19th century novel and traditions of literary realism, Tolstoy’s art consistently makes utopian gestures that, however implausible, push in directions beyond the realism of his stories. (At any rate, these gestures are more plausible than, say, the crypto-Zionism of George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda [1876]).

It pains me to say it, but it wasn’t the obvious racism of Faulkner’s art that bothered me so much when I was younger. There was plenty of that in O’Connor’s more straightforward prose. There was plenty around me in Mississippi, where I grew up. My distaste had more to do with the model of the world that novels like Faulkner’s had recreated. The world I grew up in–the world of the Deep South, late 90’s, early 2000’s–seemed both more and less than what its best writers made of it. Although I doubt I would have had the courage to say it, I felt that, more often than not, the novels I was supposed to admire ended up reproducing patterns of feeling that, for all their subtlety, tended towards inaction and despair. They ended up feeling like a prosthetic of thought rather than the thing itself.

In graduate school, I doubled down on my aversion and decided that the genre had run its course. The most interesting literary work was happening elsewhere. It had migrated from the novel to poetry again, or perhaps to film and long-form television. Or maybe the right way to think about it was that the best novels had already been written long ago, and the genre had become tired and worn out. Maybe there was nothing interesting left to be done with it.

It’s easy to form sweeping opinions like this in grad school, especially if you’re a historian working in an area like medieval and early modern literature. I had no skin in the game, so to speak. The truth is that I’m not, and probably never will be, in a position to make such a judgment, even though I did feel some vindication this week when I read that Edwin Frank, editorial director of the NYRB Classics series, has written a book that makes a more modest version of this judgment about the postwar American novel.

2

Even so, with the passage of time, I’ve come to see that some of these judgments were rooted in convictions that still seem true to me. One of these convictions has to do with the way novelists typically construct narratives. They of course deploy a host of tools to build relatively stable, durable worlds for their characters, but one of the most common of them is what the literary theorist Franco Moretti, borrowing from another famous literary theorist (Roland Barthes), has called “fillers.” Moretti argues that fillers are fictional details from everyday life that round out and ground the more climactic scenes of a novel. The easiest way to recognize them is to think of the plodding, accretive world-building of the realist novel (the “big baggy monsters” Henry James bemoaned, but also Henry James’s prose), or even an early novel like Robinson Crusoe. Stuffed in around the turning points of the plot are details from everyday life that help give those turning points their meaning or significance. Another way to think about it is to say that fillers give the plot something to turn around. Those details could be: what a character ate that morning, who showed up in the afternoon, or a character’s speculation about what Mr. Darcy’s insult might have really meant.

It would be tempting to say that fillers were part of the background of novels if they didn’t occupy so much of the foreground. Indeed, much of what passes as a novelist’s style is simply long strings of fillers that imbue the world of a novel with an idiosyncratic kind of glow. (Fillers are, like Bartleby the scrivener, “incessant in quiet action.”) In formal terms, though, it matters very little whether a novel is set in a 19th century country house in England or somewhere like a futuristic, dystopian New York. Fillers impose regularity and uniformity on the world of the novel. In terms of the claim I’m making, it doesn’t matter so much if that world is foreign or familiar to the reader. This isn’t to dismiss a novel’s setting(s) as unimportant; a setting can mark all kinds of differences. But it strikes me that the structure of most fictional narrative works in just the way that Moretti describes: a few key moments with a whole lot of filler(s) in between.

Moretti linked the emergence of fillers to the triumph of the European bourgeoisie in the second half of the 19th century. In their hallowing of the everyday, in the quiet deployment of so many fillers, novels reproduced the modest pleasures of the European middle class. Fillers function like “good manners” in a fictional narrative: “they are both mechanisms designed to keep the ‘narrativity’ of life under control – to give a regularity, a ‘style’ to existence.” And like good manners, fillers make the world stable and predictable; they “rationalize the novelistic universe, turning it into a world of few surprises, fewer adventures, and no miracles at all” (Moretti’s emphasis).1

3

It’s this last point about fillers that interests me most. Is it possible that novels, in their habitual ways of depicting and organizing sensuous worlds, frequently get in the way of the reader actually confronting their own? Might the ubiquity of fillers tempt us into thinking that the self is just like this–a whole bunch of filler plus a few crucial nuclei of experience? When I think about it, the questions strike me as quaint. It assumes that people still read novels; most don’t. But it still seems to me worth asking whether novels can do anything to help us think our way through or beyond crises like climate change or ecological collapse. And I’m not sure they can—at least, I haven’t read one that’s come close. And I wonder if the narrative dichotomy of fillers/turning points doesn’t have something to do with it.

The issue here isn’t with mimesis or representation. Lots of novels have catastrophes in them. Many sci fi and dystopian novels imagine the end of a world, or at least its partial end. The issue I’m calling attention to is the way that novels reproduce the experience of reality in narrative form. A writer could use free indirect discourse or stream of consciousness (or any host of styles and techniques) to do this. In narratological terms, though, a novel will almost always bind itself to the fillers/turning point schema. In a world dominated by global ecological collapse, does it make sense to think of a human life in these terms anymore? When did it ever? (For a much more thorough exploration of these questions, I refer the reader to Amitav Ghosh’s The Great Derangement.)

4

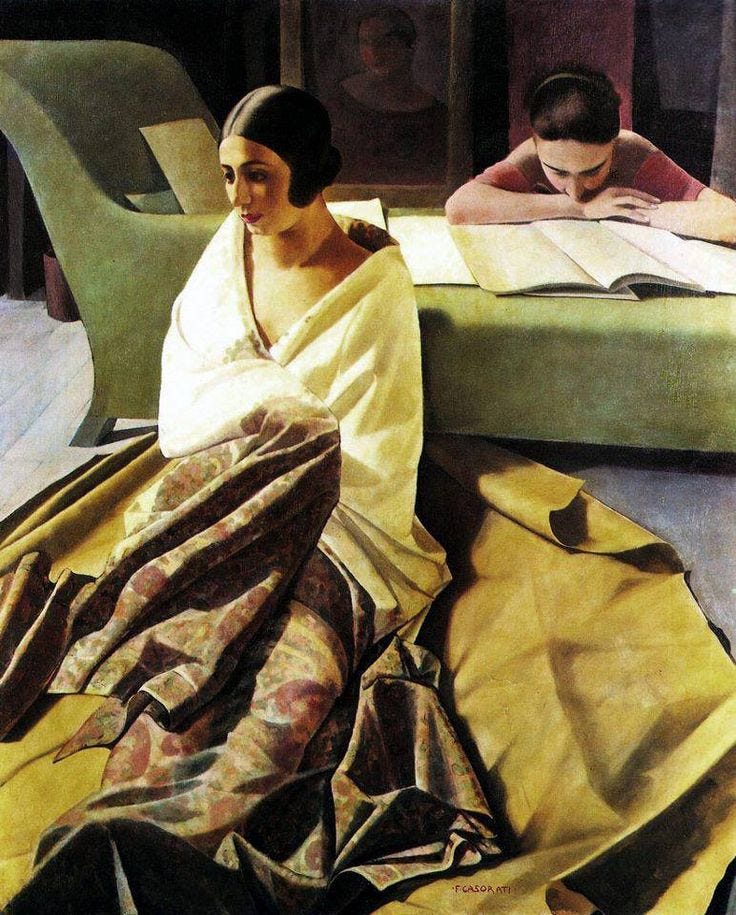

Raja [1925], Felice Casorati, tempera on board. Rome: private collection.

Over the years I have kept a running list of novels that resist the regulation of ordinary life that is central to the novel’s history. Call it the canon of the anti-novel: works of fiction that resists the fillers and turning points, or “cardinal functions” and "catalysts" (Barthes), schema. My list of anti-novels isn’t very long. To make the cut, an anti-novel has to be fun to read. (Most experimental novels aren’t.) At the end of the day, I’m not sure the list would make sense to anyone else. But near its top is a book by a 20th-century Italian novelist named Natalia Ginzburg. The book is called Family Lexicon.

From its beginning, Ginzburg’s book troubles the waters between fact, fiction, memory, narrative, and history. In the book’s preface, she makes the following series of claims:

The places, events, and people in this book are real. I haven’t invented a thing, and each time I found myself slipping into long-held habits as a novelist and made something up, I was quickly compelled to destroy the invention.

The names are also real. In the writing of this book I felt such a profound intolerance for any fiction, I couldn’t bring myself to change the real names which seemed to me indissoluble from the real people. Perhaps someone will be unhappy to find themselves so, with his or her first and last name in a book. To this I have nothing to say.

I have written only what I remember. If read as a history, one will object to the infinite lacunae. Even though the story is real, I think one should read it as if it were a novel, and therefore not demand of it any more or less than a novel can offer.

There are also many things that I do remember but decided not to write about, among these much that concerned me directly.

I had little desire to talk about myself. This is not in fact my story but rather, even with gaps and lacunae, the story of my family. I must add that during my childhood and adolescence I always thought about writing a book about the people whom I lived with and who surrounded me at the time. This is, in part, that book, but only in part because memory is ephemeral, and because books based on reality are often only faint glimpses and fragments of what we have seen and heard.

It’s hard to read paratext like this and resist asking a host of questions like: what sort of personal discipline is involved in destroying every “invention” in a story? Is invention the same thing as artifice? She says the book isn’t a novel; everything in it is real. But it’s not history either, in any straightforward sense, given the book’s “infinite lacunae.” In spite of this, we are told that we should read the book as if it were a novel, as if it were fiction, and not subject it to demands that are greater than what we demand of other novels. But that assumes that we know what we in fact demand of the novels that we read. (Pleasure? Distraction? A mirror to the world around us? All three?) And finally, what does the purported absence of fiction have to do with another one of the book’s “infinite lacunae”--the lack of any discussion of the novelist herself?

The self is a treacherous subject to write about; the sentiment is as old as Augustine. If Ginzburg had Confessions in mind when she wrote the book, then she went about writing something that takes a route going in the opposite direction of the saint. For all its attentive, nuanced exploration of family life, Family Lexicon indulges in almost no interiority whatsoever. The novel begins by tracing the strange universe of words that the young Ginzburg is born into. In the beginning, most of these words come from her father, a famous scientist and a militant socialist. He is an irascible and complicated man, doggedly committed to Italian socialism but also a racist and a tyrant in the household. He constantly bemoans the various “negroisms” the family habitually commits: “wearing city shoes on a mountain hike was a called a negroism, as was engaging in a conversation on a train with a fellow traveler or in the street with a passerby; or speaking to a neighbor from your window; taking off your shoes in the living room; warming your feet on the radiator; complaining on a mountain hike of thirst, fatigue, or blisters” (6)). Imperatives like “Don’t dribble! Don’t slobber!” accompany every meal. Dribble and slobber also describe modern painting. His colleagues at university are “imbeciles.” Most artists, especially surrealists, are “nitwits.” You are a “jackass” if you lack manners (“we children were “jackasses” when we were either uncommunicative or talked back.” “You’ve cut your hair again! What a jackass you are!” (37, 8)). The slightest trifle or thoughtless query sends him flying into a rage.

The worst of her fathers’ curses are reserved for the fascist supporters of Mussolini. They appear with increasing frequency as the lexical explorations of the novel start to pile up: “Buffoons!” “Cowards!” “Thugs!” “Negroes!” Apparently her father cannot control the volume of his voice, which makes his public and racist outbursts against fascism–often taking place in the street—all the more terrifying for the family or friends who happen to be with him.

From her mother Natalia absorbs a very different set of quips: “It’s my bitch’s sister!”; “Sulfuric acid stinks of fart”; “Here comes Hurricane Maria!”--Maria being Natalia’s middle name (41). If anyone in the family dies, their name forever takes on the epithet “poor thing.” From her maternal grandmother: “Everyday is something, everyday is something, and today Drusilla’s broken her specs” (20).

5

Are there any fillers in Ginzburg’s novel? The only way I know how to answer this question is by asking its corollary: are there any turning points? When you try to answer either question, it becomes exceedingly difficult to identify any semblance of a plot. Mapping an outline of the novel would be impossible, because there isn’t one. You might be tempted to say something like: Ginzburg’s siblings grow old; they find their own way, becoming estranged (in different ways) from their parents and from each other. But even with the book laid open on your lap, it would be very hard to point to passages when such things happen and nearly impossible to identify a series of causal relationships that lead to the given outcome.This is all the more surprising when you consider that the narrative meanderings don’t shy from the rise of fascism in Italy, the triumph of Mussolini, and the mass exile and/or deportation of Jews like Natalia, her father, and her siblings. At a certain point in the book–again, it’s difficult to say when–evading arrest and deportation become day-to-day life.

Instead of a plot, what emerges are long chains of short vignettes, sometimes a paragraph or a page long, often repeated second or third hand from Ginzburg’s mother, father, her siblings, or her friends. The form of the novel is a latticework of crossings and overlappings: single words, phrases, curses, jokes, and stories that get told and retold in strange contexts. Sometimes, the crossings occur across great leaps of time and space. The effect can be bewildering, but the form of the novel seems to respond (for this reader, anyway) to the experience of having once been a child, of having grown up and been made a stranger to one’s own family. Somehow, improbably, the words, the jokes, the memories persist, like a dead language. The metaphor is Ginzburg’s. In a rare flash of critical insight, she says this about her family’s lexicon:

My parents had five children. We now live in different cities, some of us in foreign countries, and we don’t write to each other often. When we do meet up we can be indifferent or distracted. But for us it takes just one word. It takes one word, one sentence, one of the old ones from our childhood, heard and repeated countless times. All it takes is for one of us to say “We haven’t come to Bergamo on a military campaign,” or “Sulfuric acid stinks of fart,” and we immediately fall back into our old relationships, our childhood, our youth, all inextricably linked to those words and phrases. If my siblings and I were to find ourselves in a dark cave or among millions of people, just one of those phrases or words would immediately allow us to recognize each other. Those phrases are our Latin, the dictionary of our past, they’re like Egyptian or Assyro-Babylonian hieroglyphics, evidence of a vital core that has ceased to exist but that lives on in its texts, saved from the fury of the waters, the corrosion of time. Those phrases are the basis of our family unity and will persist as long as we are in the world, re-created and revived in disparate places on the earth whenever one of us says, “Most eminent Signor Lipmann,” and we immediately hear my father’s impatient voice ringing in our ears: ‘enough of that story! I’ve heard it far too many times already!”

What is the cumulative effect on the reader of Ginzburg’s exploration of her family’s lexicon? I imagine that, over the decades, her readers have had very different reactions to it; I can’t say I’m all that very familiar with the criticism. But for me, at least, the crossings and recrossings Ginzburg pursues have a way of rendering the everyday a site of deep trauma and but also of small, seemingly improbable miracles. The ordinary isn’t hallowed; it becomes the scene of terrible violence but also the scene of dangerous acts of kindness and love. Earlier I quoted Ginzburg’s non-apology to those who find themselves portrayed negatively. When I read those lines, I can’t help but think about her father, the incorrigible racist and asshole, and yet someone capable (somehow) of extraordinary acts: hiding dissident socialists and communists from Mussolini’s police; intervening on behalf of imprisoned colleagues and loved ones; confronting fascists in public and on the street. When Turin starts being bombed, he refuses to take shelter but runs home through the streets to be with his family: “under the roar and whistle of planes, he ran hugging the walls with his head down, happy to be in danger because danger was something he loved. “Nitwitteries!” he’d say afterward. No way I’d ever go into a shelter! What do I care if I die!” (188).

The Bourgeois: Between History and Literature (Verso, 2013), 82.

Random thoughts:

-Walker Percy as the antiFaulkner?

-in the best novels the filler is the texture in the paint

-agree the impact of the novel declined in the US, but it has thrived in other countries and in immigrant and indigenous communities here

I'd love to know the rest of your short list!