Milton's Mists

Nature and labor in Paradise Lost

“What harm? Idleness had been worse.

My labor will sustain me.” Paradise Lost, X.1054-55

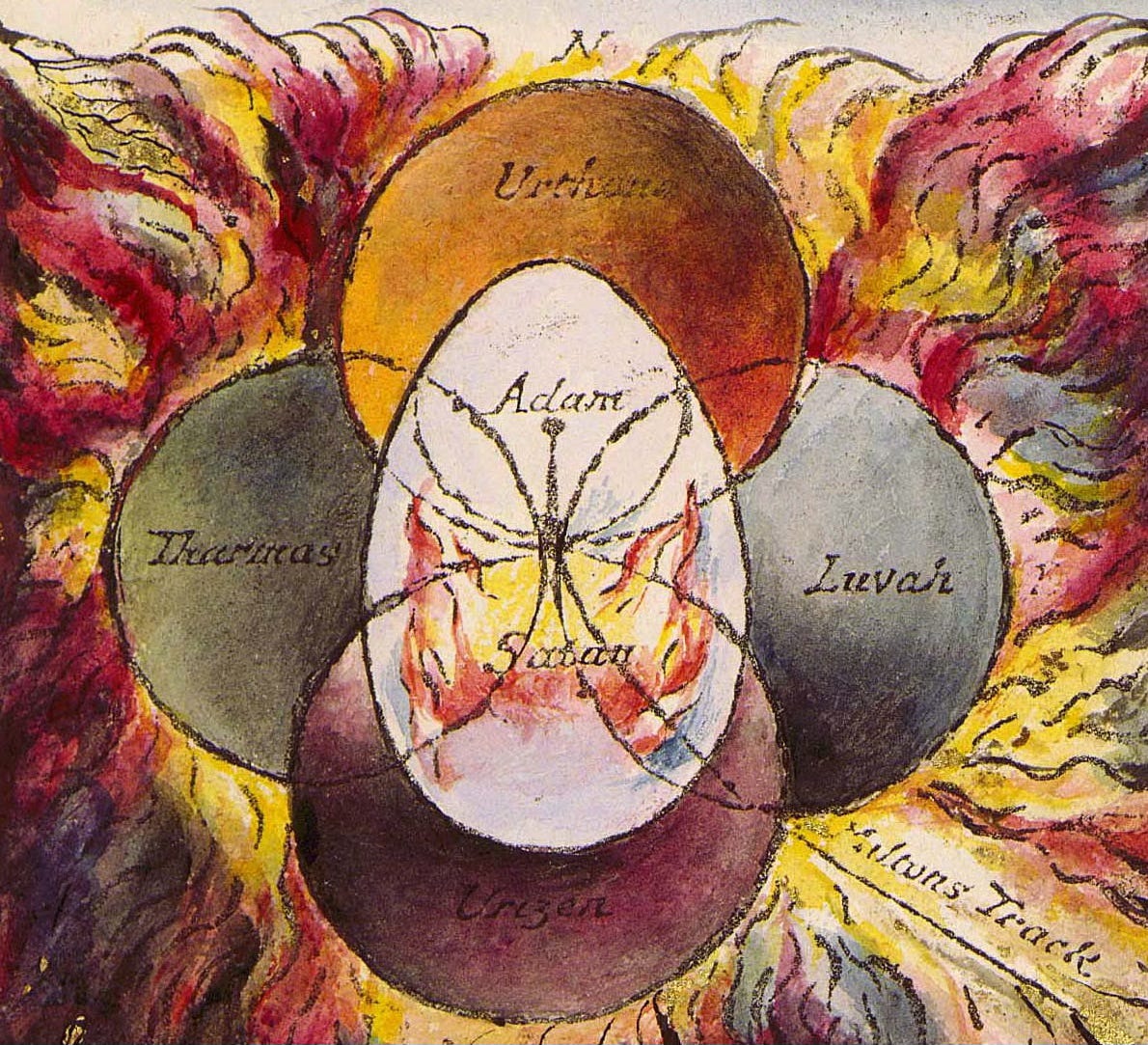

William Blake, illustration to “Milton: A Poem,” Copy A, Object 32 [Source: The William Blake Archive]

A few dozen lines from the end of Book XII of Paradise Lost, Adam is on his way out of Paradise. He has just descended a hill with the archangel, Michael, who presented Adam with a vision of the future of mankind after the fall. This vision encompassed the whole arc of salvation history: from the murder of Adam’s son, Abel, to the life and death of the second Adam, Jesus, who will one day rise “from his grave” (X.185) in victory over death.1 Then, when the vision concludes, a great host of angels, “all in bright array,” (627) comes down from an adjacent hill and joins them at the bower where Eve lies sleeping. When they arrive, Adam rouses his wife. Eve tells him that everything he saw with Michael has been revealed to her in a dream. Adam is “well pleased” at her news, but he “answered not” (625). Husband and wife stand within earshot of Michael, and so Adam prefers not to answer her. Then, the great cloud of cherubim advance

[...] On the ground

Gliding meteorous, as ev’ning mist

Ris’n from a river o’re the marish glides,

And gathers ground fast at the laborer’s heel

Homeward returning. (XII.628-32)

In a poem famous for its epic similes, this is the last one that Milton’s reader will encounter. The angelic host glides “meteorous,” or above ground, like a mist that approaches a laborer’s heel at dusk. The image is precise, but its context is undefined, especially beside the luminous “array” of the angelic host who are about to escort the first parents out of Paradise. A mist rises from an unknown river and floats over a marsh (marish), where an unknown laborer (not a peasant or a smallholder) returns home from a day’s work (we have to presume) on someone else’s farm. Who the laborer is, whom he works for, where home is: these are questions that the poem doesn’t ask. Rather, the advancing host of cherubim is simply like a gathering mist; Adam and Eve’s departure is like a laborer’s heel turned homeward.

For a brief moment, and for the last time, the poem’s reconstruction of biblical history opens outward to “everyday reality” (Kerrigan et al). But in Milton’s poem, encounters with the everyday have a way of leading back to spiritual truth. Consider the laborer’s heel. In Book X, when God confronts the erring couple, he proclaims “enmity” between Eve and the serpent: “her seed shall bruise thy head, thou bruise his heel” (X.181; cf. Gen. 3.15). One day, Milton interjects, the serpent’s head will “tread at last under our feet” (X.190). Labor is Adam’s curse: “in the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread,/ Till thou return unto the ground, for thou/ Out of the ground was taken [...] (X.204-6). In the simile, the ground, ”earth’s hallowed mold/ Of God inspired” (V.321), is mentioned twice in four lines. The mist belongs to the same treasury of allegorical cues. In Exodus, God guides the Israelites out of Egypt in a pillar cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night (e.g., Ex. 13:22). Later, he speaks to Moses from within a thick cloud (Ex. 19.9). In the Gospel of Mark, at the transfiguration, the disciples hear the Lord proclaim his favor over Jesus with a voice that came from the cloud that surrounded them (Mark 9:7).

There are many more biblical passages that Milton’s simile evokes. My point is that, in conjuring up this cascade of allusions, the simile invites the reader to perform an imaginative movement from everyday reality to a spiritual reality that lies beyond and encompasses the reader. Paradise Lost doesn’t try to negate our experience of reality or our readings of the Bible, but it does try to transfigure them. It’s hard at work on us. With the poet as our guide, we become the kind of readers who learn to labor on ourselves and the world. As Milton put elsewhere, the “true Poem” is one’s self.2 The laborer “homeward returning” is Adam, who will soon be forced to make a new home outside of Paradise. He is also every serious reader of the poem.

In her book, Labors of Innocence in Early Modern England, Joanna Picciotto argues that Milton’s methods of readerly cultivation belong to a culture of scientific and religious experimentalism in mid-seventeenth-century England. In each moment of the poem, Picciotto contends, Milton has the reader “move through [...] a site of an experiment–a contrived experience of the created world demanding diagnosis–that we [the readers] cannot help but perform” (438).3 The landscape of Paradise is less an object of contemplation than a “perceptual medium” (404) through which we might encounter the natural world as Adam first saw it. Thus, the poem itself works like an “instrument of magnification” that “help[s] us see further into the world Genesis describes” (404). The goal of poetic magnification is to transform the reader into a laborer worthy of the vocation of our first parents: to till and to keep Paradise. By moving through sacred history and encountering creation as Adam encountered it, we learn to cultivate ourselves as “paradisal ground” (409).

For many experimentalists, the new science celebrated by Francis Bacon and others promised to deliver humanity from its fallen encounters with the natural world. For centuries, creation had been shrouded in a mist of Aristotelian concepts and words. Experimentalist labor sought to pierce through the scholastic tradition and search for “means to expose the material substrate of the visible world and open it up to new kinds of cultivation” (3). Labor became the “bloodless sacrifice of a private self” that was both “interventionist and productive” (8). This program of purgation and exposure was frequently cast as a return to a potentially infinite and fecund paradise. Samuel Hartlib, who organized one of the most prominent experimentalist circles in Europe, argued that nature “hath in its bowels an (even almost) infinite, and inexhaustible treasure; much of which hath long laine hid, and is but new begun to be discovered. It may seem a large boast or meer Hyperbole to say, we enjoy not, know not, use not, the one tenth part of that plenty or wealth & happiness, that our Earth can, and (Ingenuity and industry well encouraged) will (by Gods blessing) yield.”4 In a similar vein, Francis Bacon argued that God charged all human beings “to unroll the volume of Creation” with “humility and veneration.”5 At the same time, science offered human beings “the power to conquer and subdue [Nature], to shake her to her foundations.”6

The rhetoric of Hartlib and Bacon is violent and patriarchal, but both men saw science and religious experimentalism as fundamentally continuous. So did Milton, who once called Hartib “a person sent hither by some good providence from a farre country to be the occasion and the incitement of great good to this Iland” (53).7 In a poem that takes the first three chapters of the book of Genesis as its subject matter, Milton makes creation dependent on “the infinite interstellar spaces” opened up by recent developments in the telescope.8 Over the course of twelve books, Milton mentions only one contemporary, and it’s Galileo Galilei, whom the poet claims to have met while traveling in Italy.9 Here is Milton’s famous description of Satan’s shield, which the fallen angel has slung over his back as he emerges from the lake of fire:

The broad circumference

Hung on his shoulders like the moon, whose orb

Through optic glass the Tuscan artist views

At evening from the top of Fesole,

Or in Valdarno, to descry new lands,

Rivers or mountains in her spotty globe. (I.286-291)

Up until this moment, Book I has mostly tracked the colloquy of Satan and the other fallen angels. But as Milton’s simile unfolds, our attention is drawn first to the moon and then the “Tuscan artist,” who gazes through a telescope at the lunar surface. Without warning, the simile shuttles our attention to places outside of hell: ”new lands” and vistas, landscapes of broad “rivers” and “mountains.” Multiple perspectives are in play: the eye of the poet, Galileo’s telescope, a vantage from “the top of Fesole.” The effect is disorienting, but the shifts in perspective relativize Hell and make it one more place among many in the cosmos.

***

Max Weber famously referred to Paradise Lost as “the Divine Comedy of Puritanism.” In The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Weber claimed that the poem “could not have possibly come from the pen of a medieval writer” because Milton was convinced that, through labor, mankind will “possess/ a Paradise within thee [Adam], happier far” (XII.586-7).10 In the quotation, Michael is speaking of a greater Paradise for mankind beyond Eden. The archangel is so sure of humanity’s postlapsarian prospects that he foretells a moment when Adam’s descendants will possess

[…] All the ethereal powers,

All secrets of the deep, all nature’s works,

Or works of God in heav’n, air, earth, or sea,

And all the riches of this world enjoyedst,

And all the rule, one empire[.] (XII.576-81)

Weber is certainly right to call attention to Milton’s “moral emphasis on, and religious sanction of, organized worldly labor in a calling” (42). But Paradise Lost sacralizes a very specific paradigm of labor, not a generally “secular” or worldly one. In the poem, labor is embodied, experimental, “interventionist,” and “productive.” It is also devotional. The labor of Adam is a marriage of what medieval theologians once called the vita activa and the vita contemplativa: the active life of labor, on the one hand, and the contemplative life of intellectual production on the other. But as I’ll argue in the next two essays on this Substack, labor in Milton’s Paradise is best seen as a response to a very different understanding of nature than what you find in patristic or medieval Christian doctrines of creation. Milton’s materialist theory of matter is fairly well known; animist monism is probably the best shorthand description of it that I’ve seen. He subscribed to a theology of creation ex deo, not ex nihilo. His fascination with Lucretian atomism is on full display in Paradise Lost. This welter of influences produces a vision of Paradise that is wild, profligate, and in need of human discipline and domination. Creation is also gendered; it turns out that Eve and Eden share more than just rhyming vowels.

I’ll have more to say about this in the short reflections that follow this one. For now, though, I want to end by going back to the epic simile I started this essay with. The mist seemed to chase the laborer’s heels: it gathered ground ”fast,” meaning quickly, but also perhaps close by, the laborer’s feet. In the invocation to Book III, Milton describes how “cloud” and “ever-during dark/ Surrounds me” (45-6). He asks God to “shine inward” and in his mind “there plant eyes” so that with new eyes God might “all mist from thence/ Purge and disperse” (III.52; 53;-53-4). (The poet, you may know, was blind at this point in his life.) In Book XI, as Michael prepares to show Adam a vision of the future, he must first remove a film that covers Adam’s eyes. The film “bred” (414) on his eyeballs from the “that false fruit” (413) that Eve had passed to him. Michael then pours on Adam’s eyes an ointment that he made from the herbs of Paradise. The ointment “purged” (414) “the visual nerve” (415), allowing Adam to see the long arc of salvation history.

A mist of ignorance surrounds human perception after the fall. With the right techniques and materials, we can purge our vision and learn to see the world rightly. But what of the mist around our heels and our feet?

Throughout the essay I refer to the Modern Library edition of Milton’s major works: William Kerrigan, John Rumrich, and Stephen M. Fallon, eds., The Complete Poetry and Essential Prose of John Milton (New York: Random House, 2007). I’m writing from the farm, and I don’t have easy access to a university library.

Apology for Smectymnuus, in The Complete Poetry and Essential Prose of John Milton [1642], 850.

Labors of Innocence in Early Modern England (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 2010). Also relevant are Peter Harrison’s monumental studies of early scientific inquiry in this period: The Bible, Protestantism, and the Rise of Natural Science (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998) and The Fall of Man and the Foundations of Science (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Propositions for Advancement of Husbandry-Learning (London, 1653), 3; quoted in Johnson and Wennerlind, Scarcity: A history from the Origins of Capitalism to the Climate Crisis (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 2023), 55.

The Works of Francis Bacon, ed. J. Spedding, R. L. Ellis, and D. D. Heath (London: Longman, 1857-1874) 5:132; quoted in Picciotto, 436.

“Thoughts and Conclusions on the Interpretation of Nature or A Science of Productive Works,” in Benjamin Farrington, The Philosophy of Francis Bacon: An Essay on Its Development from 1603 to 1609 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1964); quoted in Scarcity, 56.

For an example of idolatrous labor, see I.686-90, where the fallen angels pull “ribs of gold” out of the ground and “with impious hands/ rifled the bowels of their mother Earth.”

Picciotto, 436. For more on Milton and Galileo, see Marjorie Nicolson, “Milton and the Telescope,” English Literary History 2(1) (1935): 1-32).

Areopagitica, in The Complete Poetry and Essential Prose, 950. Galileo is mentioned again, and this time by name, at V.261-3.

The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (London and New York: Routledge, 2001 [1930]), 46-7.

There is so much here. Sitting in the New River Valley, shrouded in mist, contemplating labour and thinking about our heels.