On the Idea of the Tragedy of the Commons

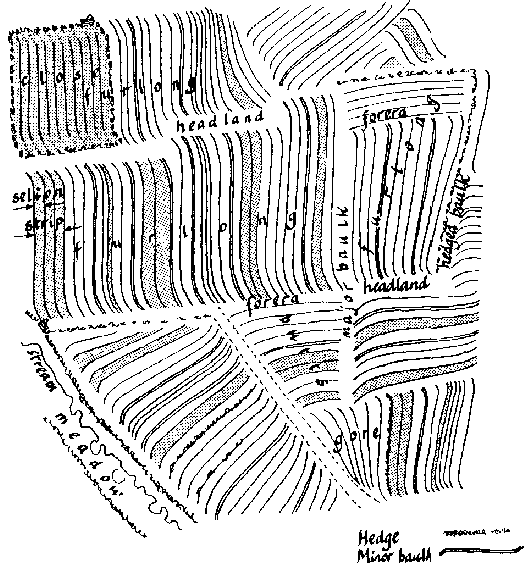

The open-field system, from An Illustrated History of the Countryside, Oliver Rackham.

When I taught undergraduates I was frequently asked to lead a survey class of British literature for students who were not or did not intend to become English majors. Students usually came to the class seeking to fulfill one of the general education requirements the university asked them to complete by graduation, requirements like a course in “language arts,” courses in a second language, or an introductory science class. On occasion I’d get an English major or minor who really wanted to enroll with me. But more often than not, I attracted students from fields like business, finance, pre-law, and pre-medicine.

I didn’t mind this so much. On the whole, my students at Wake Forest were bright and inquisitive. It didn’t matter where they came from or what I happened to be teaching them. Some days I even liked the fact that they did not have adequate training in the humanities. After all, teaching students like this afforded me insight into the formation they received in departments like business or economics that were, to be perfectly honest, quite alien to my own life and field of study. Several years later, after having started and run my own farm business that has achieved some modest success, I still don’t have much of a clue what happens in “schools of business” and the like (the discipline of accounting excepted, of course. I know why I have an accountant, and I’m glad to pay him to do what I am incapable of doing).

Anyway, in my survey class, I frequently organized the course by looking at transformations in the landscape of Great Britain, from the Anglo-Saxon period to the Norman Domesday Book, Tudor-period enclosures, and beyond. It was a brisk, helicopter-like view of poetry and prose about the land, English law, and state formation. We spent lots of time talking about common and waste land on a reasonably granular level: which regions, which counties, at what time and by whom were these places enclosed? These conversations usually focused geographically on specific writers or works. What was happening to the land around, say, the two villages where the poet John Clare lived and wrote?

Inevitably, whenever we did this, I’d have a student in each section say something like: oh yes, I know about this, the loss of commons (or waste) is a “tragedy of the commons.” To be honest, the first time I heard this comment in the course, I had never heard of the “tragedy of the commons.” When I pressed my students for what they meant, they usually answered by saying that common resources are destined to be lost because they cannot be managed competently under cooperative (or, as I would always point out, feudal) control. Inevitably you get bad actors who cheat common resources at the expense of their peers. This is merely “rational” behavior in a commons system. Fields and forests eventually get mismanaged; all producers suffer. Over time, this erodes confidence in the customary laws that protect commons. Eventually, mismanagement gives way to a system in which land, labor, and resource rights are bought and sold on the open market. If the system does not transition, then entire communities will die off. Therein lies the tragedy.

As I found out later, the tragedy of the commons is a phrase that comes from a very famous essay by an American biologist named Garrett Hardin. As a quasi-historical explanation of what (unhelpfully) get called “the enclosures,” the tragedy of the commons idea is plainly wrong. After some work together, my students had no trouble seeing why, even at the level of metaphor, the tragedy of the commons has little to no explanatory power in the complicated history of land and labor in the economic history of England. However, much later, I came to learn that the phrase has become a shibboleth for economists, public policy makers, conservationists—basically anyone who thinks about how to govern natural resources well. I don’t know how important the idea was to my students, but nearly all of them recognized the term. And it seemed to have become a mechanism for how they interpreted the world around them.

In the essay called “The Tragedy of the Commons,” Hardin imagines a piece of pasture that is open to everyone who happens to keep livestock.1 There are no apparent restrictions to the use of the land or who may have access to it. If each herdsman acts in his or her own interest, then all the herdsmen will maximize the number of cattle they graze on the pasture. Perhaps for a time “war, poaching, and disease” keep the number of animals and herdsmen down and the pasture from being overgrazed and destroyed (1244). But eventually there will come a day when, owing to the “social stability” conferred by the modern state, the number of herdsmen and cattle will grow beyond a threshold that the pasture itself can sustain. Beyond this threshold, “the inherent logic of the commons remorselessly generates tragedy” (ibid). Here is what Hardin means:

Adding together the component partial utilities, the rational herdsman concludes that the only sensible course for him to pursue is to add another animal to his herd. And another; and another….But this is the conclusion reached by each and every rational herdsman sharing a commons. Therein is the tragedy. Each man is locked into a system that compels him to increase his herd without limit–in a world that is limited. Ruin is the destination towards which all men rush, each pursuing his own best interest in a society that believes in the freedom of the commons (ibid).

Perhaps it’s helpful to note that Hardin pitches the tragedy of the commons as a rebuttal to what he calls Adam Smith’s “doctrine” of the capitalist marketplace’s “invisible hand,” whereby each economic agent acting to his own financial gain accidentally contributes to the “public interest” (ibid). For reasons incidental to Hardin’s argument, this move is more than a little sketchy. Smith mentions the invisible hand exactly once in The Wealth of Nations, and what he meant by the phrase is less than crystal clear. It was not Smith but William Paley, the English bishop, natural theologian, and apologist for intelligent design in nature, who first coined the phrase. (Paley, commenting on a bird’s maternal instinct to guard her nest, said: ”I never see a bird in that situation [...] but I recognize an invisible hand, detaining the contended prisoner from her fields and groves.”)2

Nevertheless, Hardin takes Smith’s “invisible hand” to stand for an economic philosophy in which markets regulate themselves more or less optimally and do not require a superintending force to coordinate public interest. In responding to meet a demand in the marketplace, a producer will adjust his or her output to adapt to the wants or needs of others. The cumulative effect of each agent acting in such a way contributes to the benefit of the whole: more efficiency, more meeting of needs, more “want satisfaction.” But this way of thinking ignores the material basis of production, Hardin counters. Given the problem of population growth, any resource pool is vulnerable to the “remorseless working” of the tragedy of the commons, whether it be a common pasture, arable land, a fishery, a forest, a mine, or the clean air that we breathe. While a free market might work for a time, eventually the natural resources that support the market will require privatization or protection. Put simply, “freedom in a commons brings ruin to all” (“Tragedy,” 1244).

There are a couple of things worth saying at the outset about the tragedy of the commons that Hardin envisions. The first is that Hardin presents his thought experiment as Malthusianism in modern garb. Multiple times in his short essay he invokes the spirit of Thomas Malthus, the late 18th, early 19th century British cleric who wrote several essays against the poor people of England. In the first and second essays on what he called the “the principle of population,” Malthus argued that while population grows geometrically, agriculture can only grow arithmetically. At various points in history the population of a given country will exceed its own rate of subsistence. When this threshold is reached, poverty, disease, famine, and mass death follow. But contrary to what one might think, these forces are not to be obstructed. War, pestilence, and the like were nature’s way of curbing the libidinous appetite of the less-than-rational human animal. The presence of natural evil restrains human desire. It was wrong, therefore, to provide relief to the poor. If a man marries and does not have the means to care for them, Malthus wrote, then he “should be taught to know that the laws of nature, which are the laws of God, had doomed him and his family to starve for disobeying their repeated admonitions; that he had no claim of right on society for the smallest portion of food, beyond that which his labour would fairly purchase.”3

Malthus doesn’t connect his claim about population growth to a claim about the carrying capacity of the earth. His thesis about agriculture concerns additions to the annual food supply. It’s these additions, he supposes, that can never keep up with population growth. Ever the scrupulous accountant, nature will impose penalties on producers who breed beyond their means. But even though the two men take different paths to get there, they converge in their antipathy to what Hardin calls the “freedom to breed” (“Tragedy,” 1246). And like Malthus, Hardin thinks that the problem of population growth “has no technical solution” (1243). Left unregulated, humans will eventually consume beyond the carrying capacity of the earth.

Hardin thinks there are two solutions to the dilemma of the tragedy of the commons. Both come from the outside. (1) We can either privatize the commons by dividing it up into units and giving each producer a share. Shares can be the ownership of a right to use the commons (or a unit of it) or ownership of the unit itself. (2) In cases where the resource isn’t easy to divvy up, like the atmosphere, or if it privatization isn’t an option, an administrative state must be built to monitor and regulate use. Hardin calls the former solution capitalism; the latter, socialism.

Ironically, both solutions require the constant vigilance and intervention of a strong and centralized modern state. From this perspective, Hardin’s thought experiment begins to look strange. First, Hardin insists that there are no solutions internal to the dilemma itself. Each herdsman acting in his own interest will maximize his profits to the detriment of everyone. If everyone maximizes the number of animals they can bring on pasture, everyone will suffer and the commons will be ruined. But this assumes for some strange reason that the herdsmen cannot reason with each other. If they could, they might discern a common good (e.g., the wellbeing of the commons) in virtue of which they might all stand to benefit. As the political economist Elinor Ostrom explains, if the herdsmen were allowed to enter into a binding contract and develop a cooperative management strategy, they might very well find a way to avoid tragedy. Their strategy would involve clear rules about how the pasture can be used and when, how the rules will be enforced and monitored, etc. If they were successful in doing this, the worst outcome they might endure is zero profit.4

In Hardin’s example, the constraints are such that all anyone can expect of the herdsmen is that they will maximize the numbers of animals each one has on pasture. But this is to confine the herdsmen to an unaccountably narrow model of practical reason. In Hardin’s example, all that matters is the individual herdsman’s immediate profit, not the long term benefits of his family or community or the pasture to which his animals belong. In an odd way, the commons dilemma simply restates one of the classic objections to the modern liberal state, namely, that it atomizes the individual members of communities and turns them into isolated monads of production and consumption.

This brings me to another odd feature about the tragedy of the commons. Smuggled into the middle of the commons is a deeply flawed vision of modernity and state power. In Hardin’s example, the state arises spontaneously in order to save the herdsmen from the “wars, poaching, and disease” that keep their numbers in check. This seems like a fairly straightforward recapitulation of the argument in Part I of Hobbes’s Leviathan about the need for civil authority. Without a strong, centralized state to restrain the herdsmen, they will live in a state of nature and Malthusian natural law will keep their numbers in check. But with the advent of the state and its protection of private property and basic freedoms, it is the natural world, not human beings, that suddenly come under threat. The state saves human beings from themselves, but in doing so it condemns them to a battle in the free market for increasingly scarce resources–a battle no one can win unless the state constantly surveils resource extraction and adjudicates every disagreement and infraction. The state saves us from killing each other, but it ends up conscripting us for a different sort of war: a war against nature itself.5 And like Hobbes’s state of nature, the war against nature can only be stopped through the continuous intervention of the state.

I am reminded here of what the Nazi jurist Karl Schmitt once said about liberalism: the problem with liberal politics is that it has no politics; it is merely the critique of politics. I don’t think that Hardin lands too far off from Schmitt’s outright dismissal of the liberal political tradition. After all, Hardin was a nativist who vociferously opposed immigration, and he was almost certainly a racist.6

My point here is not really to harp on Hardin’s political views, which are hardly eccentric in our own time. Rather, I’m struck by the way that market liberalism inevitably involves politically illiberal means of sustaining itself. According to the model we’ve just looked at, markets will blaze through stocks of natural resources, eventually leaving societies without enough matter, fuel, or capital to function. Hardin is hardly the first to point this out, although he may be the first to place the dilemma within an ecological framework. But my point is that, regardless of the framework, liberalism always seems to require profoundly illiberal ways of sustaining itself. Consider the anti-democratic authoritarianism of the neoliberal experiment in Pinochet’s Chile. Hayek and other architects of neoliberalism famously doubted the compatibility of so-called “free” markets and democracy. Could it be that these arrangements—free markets, unfree societies—are simply how liberalism works? Jean-Claude Michea makes this very claim in his book, The Realm of Lesser Evil.

We lack no shortage of data about the despoliation of the natural world. Practically every other news headline reminds us of the devastation our lives have wrought upon the planet. It is comforting (perhaps like all delusions) to think that ecological violence is the ineluctable outcome of economic and political systems that none of us have any say in. The language of tragedy seems to capture this experience well: after all, what can you or I do? But the consequences of such an attitude are more than the world can bear. Despair ends up requiring us to place our faith in institutions that have failed utterly to make good on any of their promises. Might this not be a moment for the emergence of cooperative institutions? And could those institutions light the way to new forms of political governance?

https://pages.mtu.edu/~asmayer/rural_sustain/governance/Hardin%201968.pdf

John Bellamy Foster, Marx’s Ecology: Materialism and Nature (New York: Monthly Review Press, 85.

Foster, Marx’s Ecology, 88.

Ostrom, Governing the Commons (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990) 4, 16. Accessed here: https://www.actu-environnement.com/media/pdf/ostrom_1990.pdf

Ostrom, 12

www.splcenter.org/resources/extremist-files/garrett-hardin/