Quo tempore primum

Thoughts in and out of season

The other day I heard a farmer say that as the years go by, each season seems to disclose more and more of its own personality to him. Farming taught him to recognize the changes that herald the arrival of a new season. But with each season’s arrival, there is something new, a variation in the pattern, that feels unexpected and different. In particular, spring rarely feels the same from one year to the next. Perhaps it is because now, after having farmed for over a decade, he is more attuned to the subtler signs of spring. Or maybe it’s because there are also changes happening within him, year to year, that the end of winter helps him recognize. Sometimes it can be difficult to know where exactly the changes are happening, within or without, and how one should go about drawing a line between the two in the first place.

On our farm, spring arrived this year in a tumbling cascade of grasses and blossoms. In March, the weather turned warm quickly, reaching temperatures of eight-five by the middle of the month, before dipping back down to the fifties mid-day and to overnight lows that hovered, mercifully, just above freezing. It felt like the sun had woken up early with a burst of energy but decided that, on second or third thought, perhaps it was better to slip back under the covers. But those few days of warmth provided enough heat and light to force a burst of growth. After an autumn in which my animals grazed the pastures down to the nub, the grasses are finally long enough again to be pressed down and folded by the wind. About six weeks ago that I saw them wimpling in the field. The emergence of the redbud blossoms happened early, too: the deep purples and pinks, aching in the trees. And the downy white dogwood flowers peering up from the creeks and bottomland. The oak catkins quivering in the wind. I see and recognize these things. By the end of the week, they’ll all be gone. But I can’t say for certain that I’ve noticed their splendor begin and end together, in concert, all at once.

Has it ever been so, the unique personality of each season, of fall, winter, spring, and summer? Or could it be that, in an increasingly unpredictable climate, the uniqueness of this year’s spring belongs to new patterns we haven’t seen before, patterns of unravelling and unpredictability? I’m not wondering what it would be like to have no spring; I don’t think that’s coming any time soon. I just mean: might the variations in the pattern from year to year be something different from what previous generations have experienced? And instead of inspiring self-loathing, or a hatred for what our species has done to creation, might they invite us, observers and agents in the world, to become more intimately acquainted with the proclivities of the flora and fauna that surround us?

***

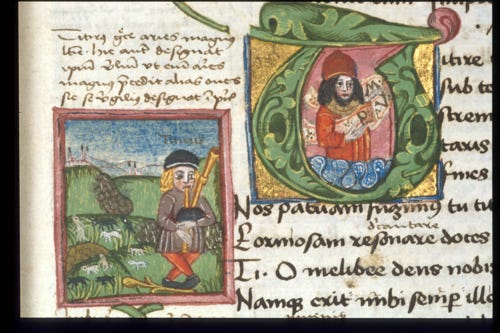

Opening of Virgil's Eclogues, detail of Burney MS 272, f 4r. [Source: British Library website]

Every spring I read through the four poems by Vergil (70-19 BC) that make up the Georgics (from the Greek, georgika, meaning “farming things”). The Georgics are a Roman agricultural manual dressed up in beautiful hexameter lines. Many have questioned the poems’ actual usefulness for agriculture. But that hasn’t stopped its readers from trying to implement Vergilian advice in their fields and pastures. In 1724, the English poet, William Benson, proclaimed that there was more Vergilian farming going on in England at that time than there was in Italy. The practice of taking Vergil to the fields was exceedingly popular in the Netherlands, too, where the Georgics was first translated into Dutch in 1646.

It’s true that there is plenty of bad advice in the Georgics–-particularly in the third one, which concerns animal husbandry. But there’s good sense elsewhere, like why and how to go about spreading animal manure and the ashes of your hearth on your vegetable or wheat crops (each excellent sources of nitrogen and potassium), or how to tame wild bees (fourth Georgic). But I’m not seeking practical advice when I turn to Vergil every year. I love these poems because they describe a world that’s brimming with of signs and wonders that, if read properly, help human beings maintain a foothold in a world that is always “ready to get worse, lapse backward, fall away from what [it was]” (sic omnia fatis/ in peius ruere ac retro sublapsa referri) (I.17).

My favorites are the first Georgic, about farming annuals like wheat and barley, and the second, on farming perennials like grape vines and tree crops. In both, Vergil insists on the importance of a farmer learning how to read the signs of changing seasons and future weather. When the late winter winds begins to crumble the clods of soil in the field, the farmer knows it’s time to drag the heavy furrow across them. If the wild almond trees are full of blooms in May, it means that the farmer can expect a bounty of wheat in the fall. If they are mostly full of leaves, the farmer should prepare for the possibility of a lost crop. “No storm comes on without a warning,” Vergil advises; pay attention to “signs of swelling and heaving” in the water, or gulls flying landward in the wind, or the heron deserting “its own familiar marsh” (31). Nothing is more important, though, than paying attention to the behavior of the stars. You should always wait to plant corn, wheat, or spelt after the Pleiades “take their leave of the morning sky” (I.19). The seventeenth day of the spring months is a good day to plant vines, break in oxen, and prepare the loom. Try to avoid the fifth of the month, the day when the Titans tried to overthrow Uranus, the god of the Heavens (I.25).

Lurking behind each piece of advice is the Lucretian dictum, “felix qui potuit rerum cognoscere causas”: happy is the one who was able to know the causes of things. The wise farmer is the one who has learned to recognize the signs that nature gives him. These include (perhaps especially) variations in the pattern of natural causation. When blotchy, garish colors flame around a setting sun, expect the next day “to boil and seethe with storm” (I.37). If the wick of your lamp suddenly sputters and absorbs on a dark, smelly substance, then rain is coming soon. Be really worried when wild animals start making sounds that sound like human voices.

***

I’m not one to match music to a particular season or a mood. But lately, our family has been exploring the music of Henry Threadgill, a free jazz composer and instrumentalist who hails from Chicago, and I thought I’d share some recordings we’ve enjoyed. In early December, jazz critic Adam Shatz published a review of Threadgills’ new memoir, Easily Slip into Another World: A Life in Music, in the New York Review of Books. In the review, Shatz describes Threadgill as the avant-garde heir to an American Romantic musical tradition. I’m not sure how he’s envisioning this tradition, or how exactly it intersects with the black aesthetic traditions of the 20th century. To be fair, it’s a review of a memoir; there’s only so much you can do. But Shatz claims (persuasively, I think) that Threadgill’s experimentalism is in search of “an experience of musical beauty that, because of its unfamiliarity, inspires an awe that’s hard to distinguish from terror.” The allusion is to Kant’s theory of the sublime; I was reminded of this quote from the Critique of Judgment: “the straining of the imagination to use nature as a schema for ideas…forbidding to sensibility, but which, for all that, has an attraction for us, arising from the fact of its being a dominion which reason exercises over sensibility with a view to extending it to the requirements of its own realm (the practical) and letting it look out beyond itself into that infinite, which for it is an abyss,” (part 8). “Forbidding to sensiblity” sounds about right. Have a look at this clip from one of Threadgill’s ensembles, The Society Situation Dance Band, performing live in Hamburg in 1983. In the video, Threadgill directs. A cello solo begins at the 8:00 minute mark or thereabouts.The player is Dierdre Murray, one of Threadgill’s longtime collaborators, and an outstanding jazz and classical musician in her own right. It’s irreverent, dissonant, deeply serious.

Shatz describes Threadgill as a magpie, and you can see it in this performance. At different moments, the afrobeat rhythm slips into in a James Brown-like syncopation or dixeliand rag. New Orleans-style brass mingles with dissonant swells from the string section. It’s musical pastiche, but there’s not a hint of send up or irony.

I read Virgil's Georgics for the first time this spring. It is very beautiful, but I did think some of it strange advice.

I have been enjoying reading your articles the last few months, and was pleased to find another Thomas Hardy fan!