Weird Fruit: Henry David Thoreau, John Evelyn, and the Idea of Agriculture as Worship

Thoreau's Kalendar project and its early modern roots

During the last two years of his life, Henry David Thoreau worked diligently on a project that he referred to in his journals as “my Kalendar.”1 Alternately botanical, climatological, and geologic in scope, the Kalendar synthesized a lifetime of observations about the flora, fauna, and climate of Concord, Massachusetts, and its surroundings. Thoreau never came close to completing it, but from a fairly early date he planned for his observations to be assembled into a monthly, multi-volume almanac organized by topic—perhaps not so different from the form of Walden itself, a text organized by keyword and unfolding over the course of a single calendar year. What made it different from this earlier work was that Thoreau would focus exclusively on what happened to the river, to the sky, and to the trees from week to week and month to month over the course of the year. Thoreau, the man, would assume a place somewhere in the background. The new project would place nature itself front and center. In his essay, “Walking,” Thoreau put it this way: “Henceforth we would write a literature which gives expression to Nature […] He would be a poet who could impress the winds and streams into his service, to speak for him.”2 One measure of Thoreau’s seriousness about his Kalendar is that, for the days leading up to his death, entries appear in his journal that record the height of the Concord River. On those days he was bedridden with illness, so he must have had friends go and record the measurements on his behalf.

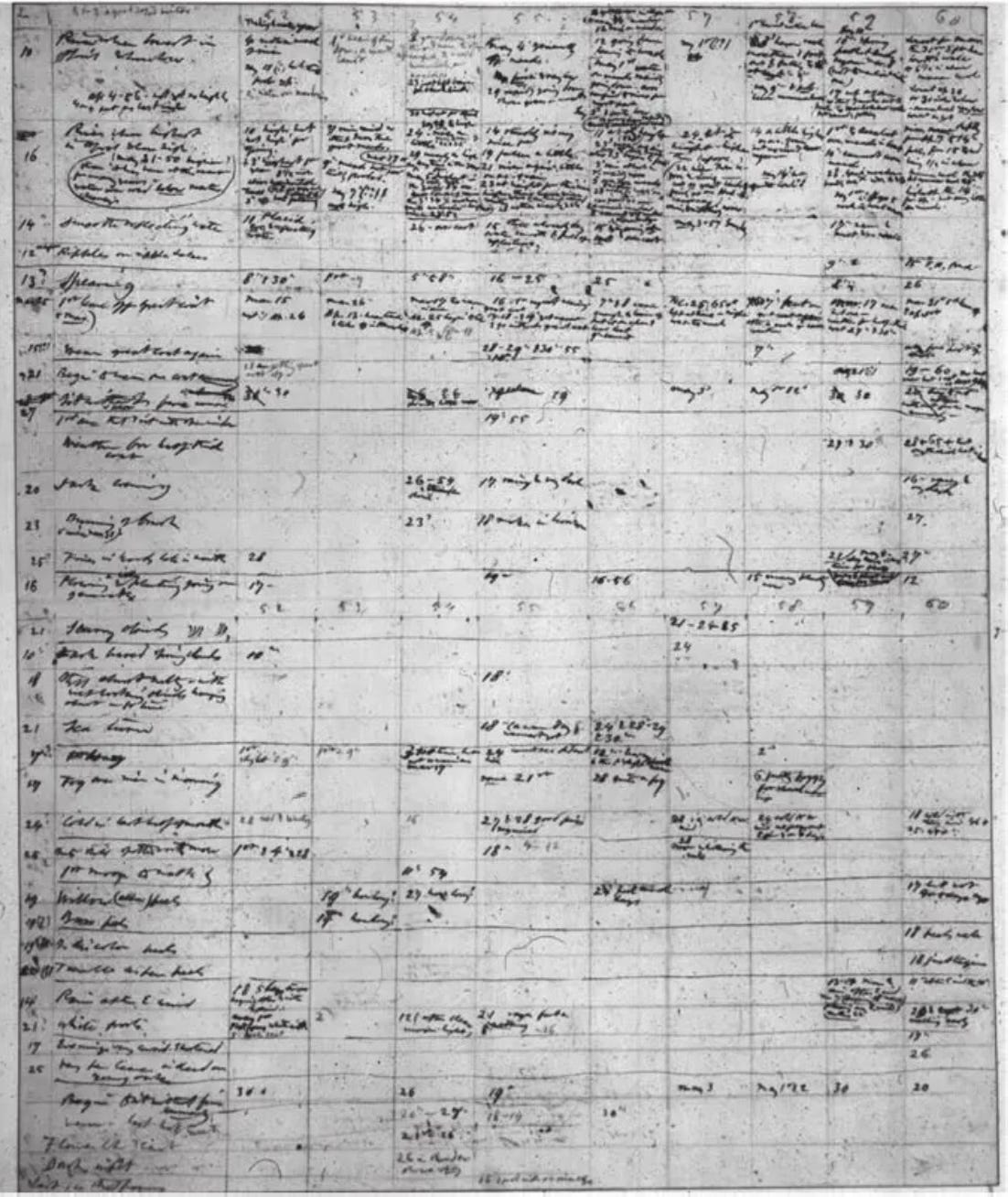

An image from Thoreau’s Kalendar project.

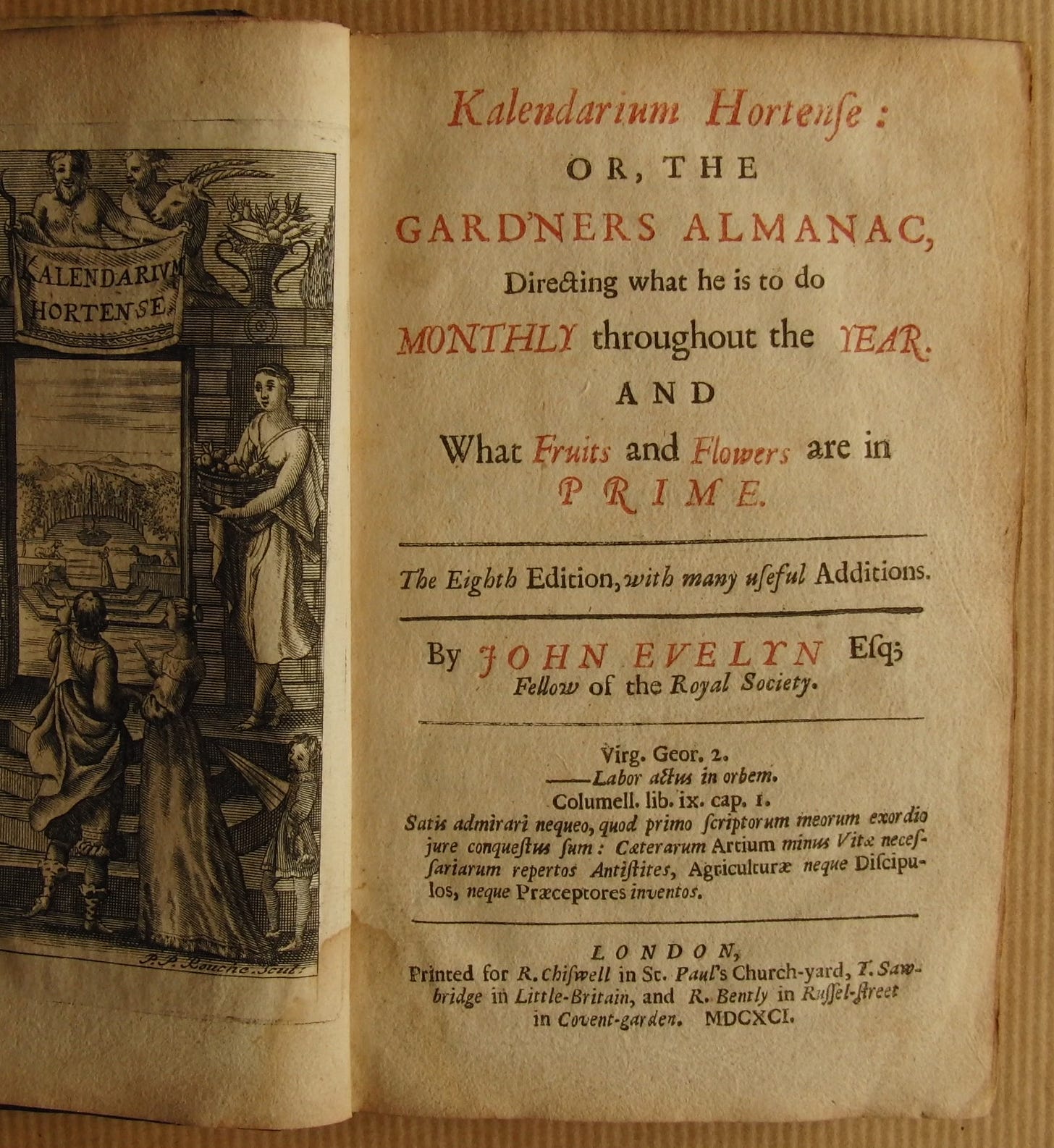

The title Thoreau used for his project is borrowed from the title of a treatise called Kalendarium Hortense, a botanical manual and almanac by the seventeenth century experimentalist, author, and founding member of the Royal Society, John Evelyn [1620-1706]. In his journals, Thoreau was so insistent upon making the connection with Evelyn explicit that, when he accidentally writes the modern spelling of calendar, he emends the text by crossing out the “C” and replacing it with the deliberately antiquated spelling. Thoreau says that he read and enjoyed the Kalendarium in early months of 1852, but he must have been a reader of Evelyn’s work from a relatively early date.3 Evelyn’s name pops up in several key passages of Walden that date to the earliest draft of the text, 1846-7—“the Bean Field” chapter, which I discuss here and will do so again soon, as well as several other places. Evelyn shows up in the journals of the 1850’s, too, going so far as to supply Thoreau with a recherché model of project he wanted to compile the last years of his life. And yet, as far as I can tell, only a handful of scholars have treated Thoreau’s engagement with Evelyn seriously (three short articles from 1960, 1967, and 1971, respectively).

Part of the difficulty stems from Thoreau’s own development as a thinker. Scholars of Thoreau often note the slow drift in the journals away from Emerson’s Romantic Neoplatonism to a materialist approach to the observation of natural phenomena. In 1850, his relationship with Emerson buckled, in part due to the intimate friendship Thoreau maintained with Lidia, Emerson’s wife. Thoreau’s departure from the Emerson household preceded a long, slow divestment from the transcendentalist project of discerning higher, spiritual laws through a humble, if not naive, engagement with the natural world. In Seeing New Worlds: Henry David Thoreau and Nineteenth-Century Science [1995], Laura Dassow Walls argued that Thoreau’s disentanglement from the Emersonian project was caused in part by Thoreau’s engagement with the writings of that “Napoleon of science,” Alexander von Humboldt [1769-1859]. The fruit of reading Humboldt was a “proto-ecological” vision of human and natural entanglement.4 Journals from this period show a rejection of Emersonian abstraction in favor of a more relational way of knowing and encountering the natural world. Dassow Walls calls Thoreau’s post-Walden achievement an “epistemology of contact,” a sustained scientific delighting in the “raw materials” of the nature as opposed to the practice of transcending them for the higher, eternal laws that she associates with Coleridge and Emerson. The role of the scientific observer is simply to record details and make connections between them. Perhaps some deeper purpose will shine through, but only after a lifetime of meticulous, patient study. In a similar vein, Lance Newman sees an “unrelenting facticity” to the journals from about 1846 on.5 Newman suggests that this facticity is mirrored in an increasingly materialist cast of Thoreau’s social criticism. “As Thoreau moved increasingly toward a materialist understanding of nature,” Newman writes, “he applied this same mode of analysis to the capitalist social order, and was therefore was driven more and more toward radical political conclusions.6

Whatever the precise implications of Thoreau’s materialist turn, the casual reader of Walden will be struck by the late journals’ absence of the man from the recorded minutiae of Concord’s flora and fauna. But Thoreau, even at his most scientific, comes nowhere near a Darwin or a Karl Marx. Perhaps the last, nearly complete text that he wrote—a six-hundred-page tome, intended for the Kalendar project, that bore the handwritten title “Wild Fruits”—is all about how to harvest wild berries and nuts with your friends (and the spiritual benefits of doing so). In this surprisingly comprehensive text, the most revolutionary provocation you will find is Thoreau’s suggestion that towns and cities ought to maintain a orchard-like “commons” of wild fruit trees for its citizens, free of charge—not a bad idea, by any means, but hardly the sort of thing one would expect from a devotee of Humboldt or Darwin, whose Voyage of the Beagle [1839] and Origin of the Species [1859] Thoreau devoured nearly as soon as they washed up on American shores.

This only makes Thoreau’s obsession with John Evelyn’s writings even more curious. From a certain perspective, John Evelyn is about as far away as you could get from Alexander von Humboldt, the “Napoleon of science,” or Charles Darwin’s impersonal micro-studies of species development. An early experimentalist and disciple of Francis Bacon, Evelyn was fascinated by the metaphysics of soils, plants, and climate. But he addresses natural phenomena with an eye towards actively recovering Eden in the gardens and forests of seventeenth-century England. As he explains in his Sylva [1662], probably the first treatise written on the practice of agroforestry, in forests one finds “the very Infancy of the World in which Adam was entertained in Paradise.” He points out that in the second creation narrative of Genesis, God intended trees to be Adam’s first companions, not woman (cf. Gen. 2:4-18). “The Sum of all is,” Evelyn continues, “Paradise itself was but a kind of Nemorous Temple, or Sacred Grove, planted by God himself, and given to Man, tanquam primo sacerdoti [as the first priest], a Place consecrated for sober Discipline, and to contemplate those Mysterious and [143] Sacramentall Trees which they were not to touch with their Hands.” For Evelyn, the implication of the Genesis narrative is that, through careful study and experimentation, humankind might return to such an Edenic state as Adam himself experienced. Here is Thoreau’s response to this text, having re-read Sylva, dated June 9th, 1852: “[Evelyn’s] “Silva” is a new kind of prayerbook, a glorifying of the trees and enjoying them forever, which was the chief end of his [that is, Evelyn’s] life.”7

A new kind of prayerbook, indeed. Thoreau’s remarks on Sylva parody the first question and answer of the Westminster Shorter Catechism [1646-7]: “What is the chief end of Man? To glorify God, and enjoy him forever.” This was a text written in the brief (and failed) attempt to bring the Church of England into alignment with Scottish Presbyterianism—a few years before the execution of Charles I, when Evelyn was busy experimenting with trees and sharing discoveries with the members of Samuel Hartlib’s circle. I take Thoreau to be making the suggestion of alternative pathways for the development of Christian theology in the seventeenth century, pathways Presbyterians—and the Puritans of the New World, and the “mass of men” of nineteenth-century America—might have taken and might still take up. This is a path that Evelyn took up, Thoreau implies, and it is what Thoreau sees himself as having done in Walden and indeed his own life’s work.

In Senses of Walden, the philosopher Stanley Cavell argued that Walden is designed to function as a new sacred scripture for a nation hovering like a ghost at the crossroads of democracy and industrial capitalism. The letter of the Thoreau’s text frames the man’s experiences of living on the shores of Walden Pond and among its trees. But as anyone who has read the text knows, Walden constantly gestures to what it calls “higher laws,” Nature’s sensus spiritualis. Cavell writes: “Walden’s puns and paradoxes, its fracturing of idiom and twisting of quotation, its drones of fact and flights of impersonation—all are to keep faith at once with the mother and the father, to unite them, and to have the word born in us” (16). It strikes me that, for all its “drones of fact,” the Kalendar project only makes sense in the context of the ecological conversion that Walden figures forth and asks—demands—its readers to undergo.

In part 2 of this essay, I’ll look briefly at some of Evelyn’s life and writings, and then loop back one more to the famous passage in Walden where Thoreau appears to use Evelyn’s advice about working the soil. Stay tuned.

e.g. Journals, 485; Dassow Walls, A Life, 435.

Seeing New Worlds, 147; NHE, 120, “Wild Fruits,” introduction, xii.

Journals, 132-3.

18, 144.

Our Common Home, 162.

170.

Journals, 132.